Simply put, is the equation, “Spend more, get less” a sustainable business model?

Of course not. But that’s the simple math on U.S. health care spending and what comes from it, according to Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly, a perennial report from The Commonwealth Fund that compares health system performance across eleven developed countries.

Of course not. But that’s the simple math on U.S. health care spending and what comes from it, according to Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly, a perennial report from The Commonwealth Fund that compares health system performance across eleven developed countries.

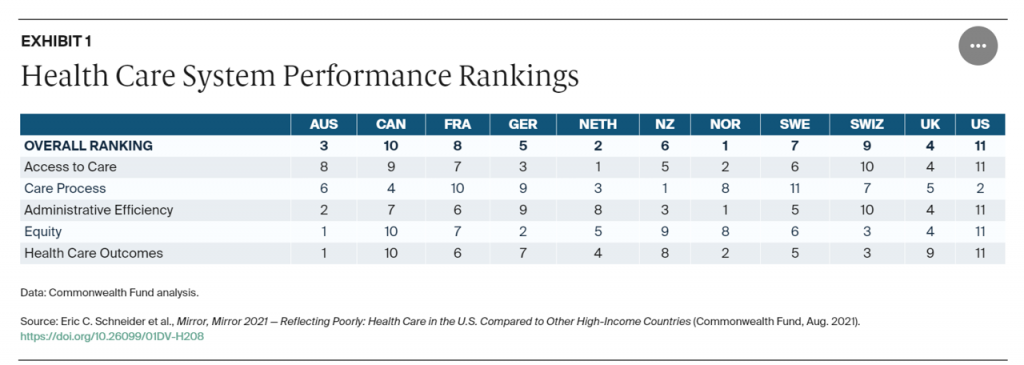

The first table details the metrics that the Fund compares across the eleven peer nations, which included Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The metrics compared were access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes.

The U.S. ranked number 11 out of 11 nations with the exception of care process, based on four pillars: preventive care, safe care, coordinated care, and engagement and patient preferences. More granularly, prevention encompasses screening, counseling, and rates of avoidable hospital admissions for diabetes, asthma, and congestive heart failure. Compared with the ten other countries studied, the Commonwealth Fund placed the U.S. in second position just behind New Zealand which topped the list for care process.

Otherwise, America ranked dead last in the four other categories, placing it in overall last place for health system performance among other wealthy countries.

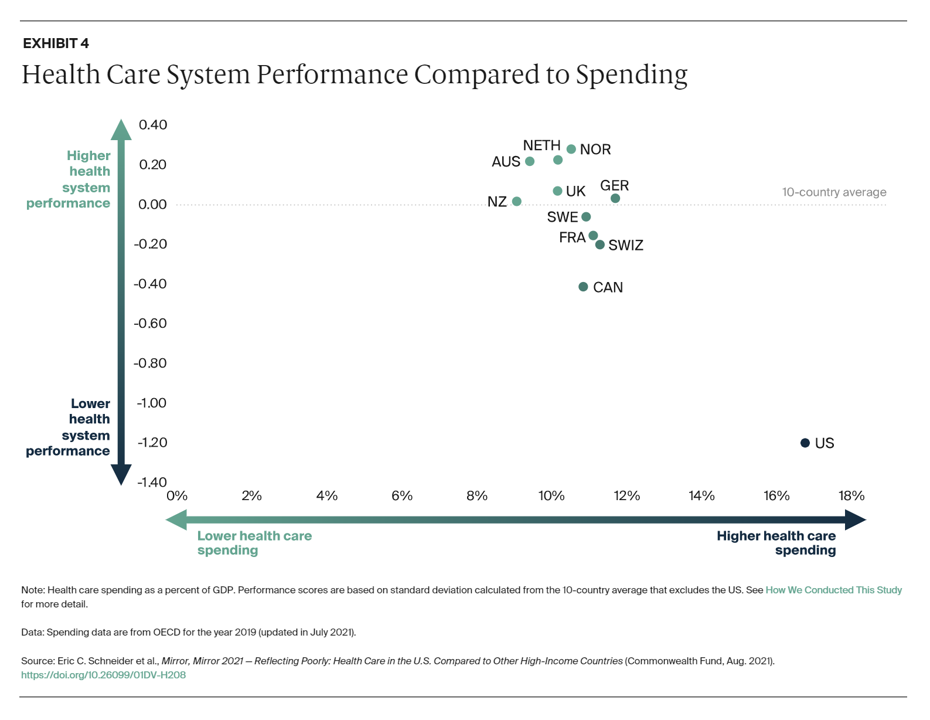

Spending the most money (as a percent of gross domestic product) does not translate into high health care system outcomes, this study concludes.

Spending the most money (as a percent of gross domestic product) does not translate into high health care system outcomes, this study concludes.

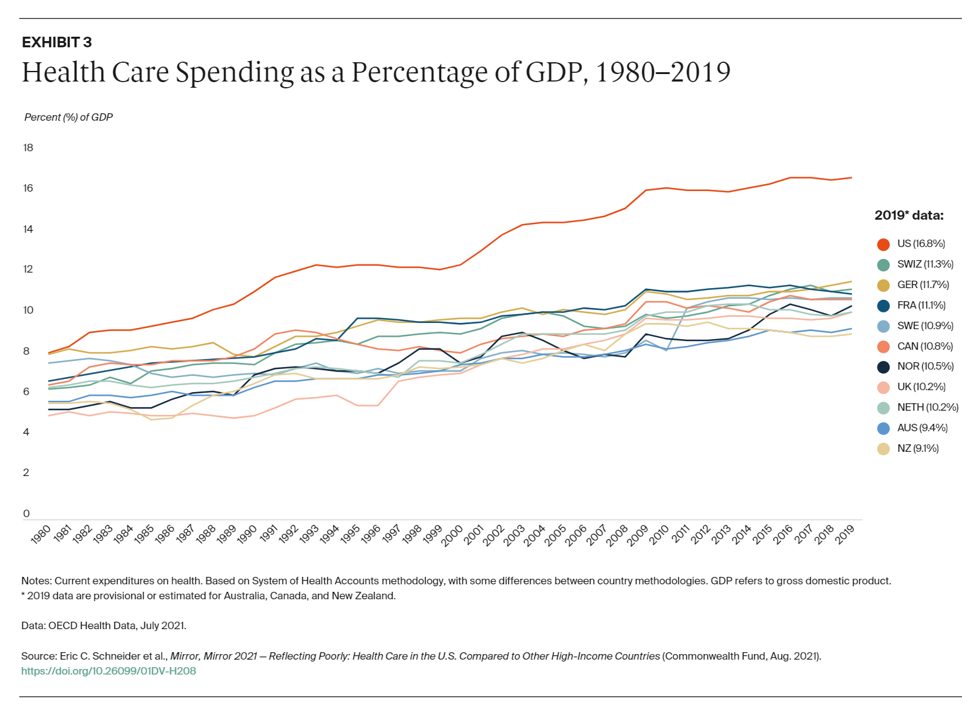

The second chart illustrates the long-time fact that the U.S. allocates more national spending to health care than any other country (among these OECD nations as well as countries not included in this research).

We’re #1! we Americans can chant, when it comes to medical spending. In 2019, that reached nearly 17% of the national economy.

Not-so-close behind the U.S. for health care spending as a proportion of GDP are Switzerland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Canada, and France, all of which allocates between 10 and 12% of GDP to medical costs.

These are all countries that provide their health citizens some flavor of universal health care coverage. There are differences in financing and delivery underneath that access-for-all, but the intent is that every resident is a health citizen with care as a civil right. s

s

What do these nations get in return for allocating one-tenth, or just a bit more of their countries macro-economies, to healthcare?

The third chart gives us a mass of dots in a general region around “higher health system performance and not-so-different levels of health care spending — a range of 9% (for New Zealand and Australia) and closer to 12% for Germany and Switzerland.

You can miss the U.S. data point if you blink or keep your eyes in the upper middle quadrant of the chart. The dot/data point for the U.S. is found at the lower right corner of the graph, with ultra-high health care spending and relatively low heath system performance.

That bottom-line is that the U.S. gets a pretty poor return-on-investment for health care spending based on the five metrics analyzed.

For the U.S., key detractors from good performance on these measures include:

- Lack of universal access to care for all Americans (the Fund points out that 30 mm people in the U.S. were still uninsured and 40 mm with under-insured situations, as well as millions of insured Americans facing greater unaffordable out-of-pocket costs)

- Less adequate primary care “backbone” with large gaps in PCP coverage throughout the United States

- High administrative spending relative to the other countries, as fragmented insurance systems and payors generate too much paperwork (real “paper” and wasted digital work-flows), along with too-much-time spent by clinicians with poorly-designed EHR and other digital tech

- Insufficient spending upstream on social care and determinants of health risks (SDoH), shown in the chart, where the U.S. spends a much lower (inverse) proportion on social care compared with healthcare in other peer nations (again, using the latest OECD data available).

This chart comes out of my book, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen, where pre-pandemic, I made the argument for Americans to evolve beyond consumers to full-on health citizens with the rights of health care, digital privacy and security, and a new social contract of love and respect for fellow health citizens.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: This analysis must be placed in the context of the coronavirus pandemic, which is impacting both the fiscal health of the U.S. as well as the physical and mental health of the nation’s health citizens.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: This analysis must be placed in the context of the coronavirus pandemic, which is impacting both the fiscal health of the U.S. as well as the physical and mental health of the nation’s health citizens.

Furthermore, in the specific context of the annual 2021 convening of HIMSS, bringing together the world’s stakeholders in health care and digital technology, the implications are many, complicated, and some uncertain.

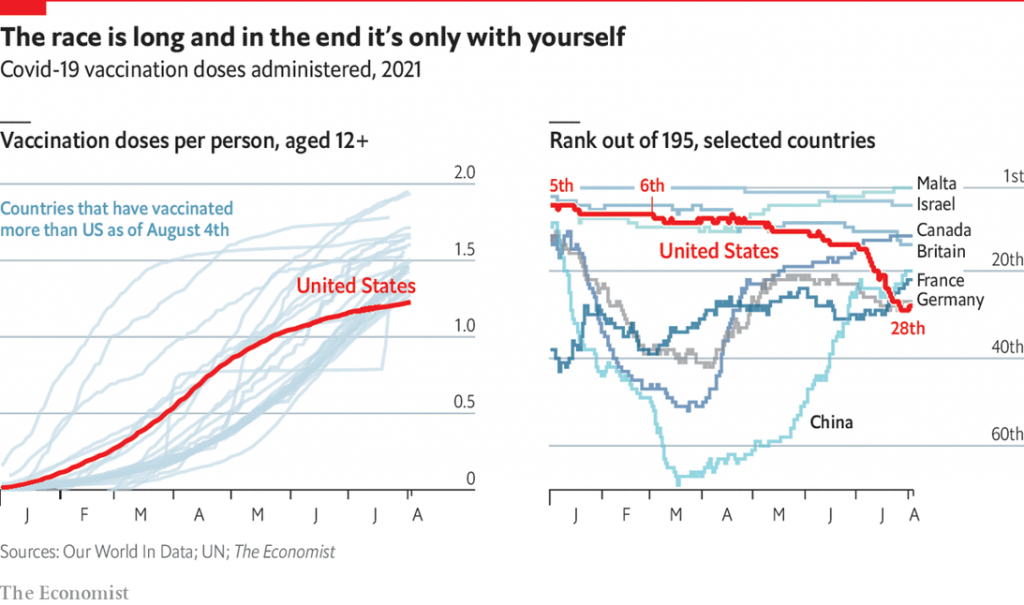

In the diagram here titled “The race is long,” the clever information journalists at The Economist magazine show ill that the race of vaccinations administered in the U.S. really fell off beginning in late June, now ranking 28th behind those countries discussed in the Commonwealth Fund report along with many others like Malta and Israel which rank top of 195 nations. Even China has lately exceeded the U.S. vaccination rate of doses administered.

In FitchRatings’ report, US Healthcare System to Expand, Adapt to Long-Term COVID-19 Fallout, published 28 July 2021, the firm observes:

“For healthcare providers, the expansion of the healthcare system over the long term will likely exacerbate traditional pressures on operating performance such as tight labor and wage markets for experienced staff, rising pharmaceutical expenses, and supply costs in general….the ultimate story of the pandemic is still being told. The infection rate is once again trending up, presumably due to a combination of factors including a dramatic reduction in demand for new vaccinations, the rapid spread of the more infectious Delta variant in the U.S., as well as the reduction in mitigation measures.”

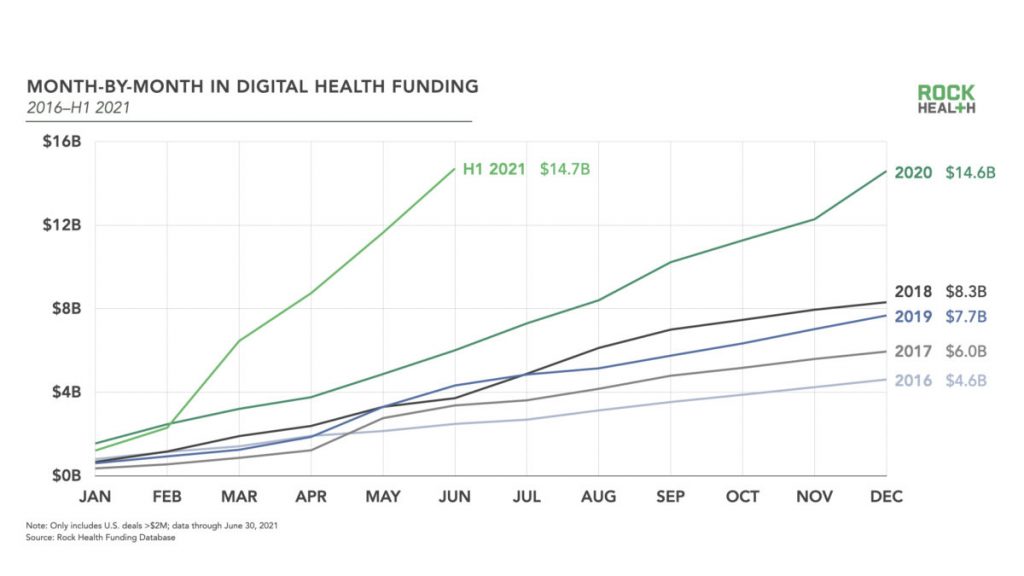

It’s interesting that Rock Health’s digital health funding line graph echoes the left side of the Economist graph. Look at the sharp hockey-stick growth of digital health funding in JUST the first half-year of 2021 compared with 2020….the slope is rising much faster, exceeding the full-year total digital health funding level hit last year.

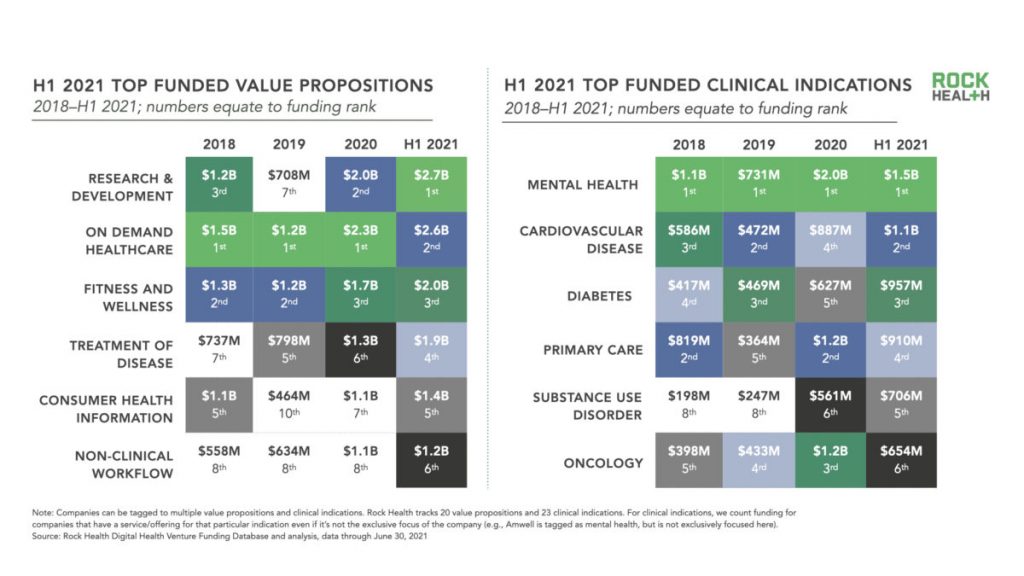

The pandemic has accelerated funding in digital health tools across many forms, shown in Rock Health’s second chart here on top funded value and clinical propositions.

The pandemic has accelerated funding in digital health tools across many forms, shown in Rock Health’s second chart here on top funded value and clinical propositions.

To answer my over-arching question — can digital health help improve health system performance in the U.S. — it’s a qualified “yes.” That promise will yield an ROI if the health system will re-allocated resources toward value, away from volume, while driving paper-based wasteful processes out of transactions, enable greater self-care in peoples’ hands at home and in the community in lower-cost settings, and invest more upstream in social care and away from avoidable tertiary care and duplication of services.

My colleagues know I’m an optimist, and many will say I’m naive even to write this, echoing a Holy Grail I’ve spent many years working toward. Earlier this week, one of those long-time collegial friends responded to my tweet @HealthyThinker about the Commonwealth Fund study that the U.S. health care system, “was designed to work this way.”

True, U.S. health care financing has operated like a whac-a-mole-game, pressing down on payments in one segment only to find the next year that revenues rise in an adjacent area.

Digital health tools can help alleviate some of our challenges: Rock Health notes that investments in on-demand healthcare, fitness and wellness, treatment, and information all grew past $1 billion as much as $2.7 bn for on-demand care by July 1st, 2021. Mental health, long-underserved, garnered a great deal of in-flow; primary care, long under-funded, less than $1 bn but still, attracting investment from interesting places like Morgan Health and for new primary care business models.

We can’t ask health care stakeholders, whether providers or IT developers, to do all the heavy lifting of building American healthcare back better, more cost-effectively, and equitably. That’s what government regulation and intervention are for, to make more fair and effective the lack of a real health care market.

In the immediate term, looking from “now” to one and three years from now, we can expect the private sector to take on more public health roles. This will be the case, especially in the wake of COVID-19, a K-recovery that has exacerbated income inequality for those health citizens at the lower-end of the economic spectrum, and so many health care providers now facing a new wave of an “unvaccinated epidemic” of coronavirus patients in hospital beds.

I’ll be doing my best to identify some case studies and innovations that address these issues during #HIMSS21. I’ll be attending from afar, virtually and digitally, also speaking via phone and Zoom and Teams with some of the vendor representatives I’d have met with in-person were we all attending live. Stay well, everyone, in Las Vegas and in your neighborhoods, as we all do our best to come through this pandemic journey together in joy and good health.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.