When a new technology or product starts to get used in a market, it follows a diffusion curve whose slope depends on the pace of adoption in that market.

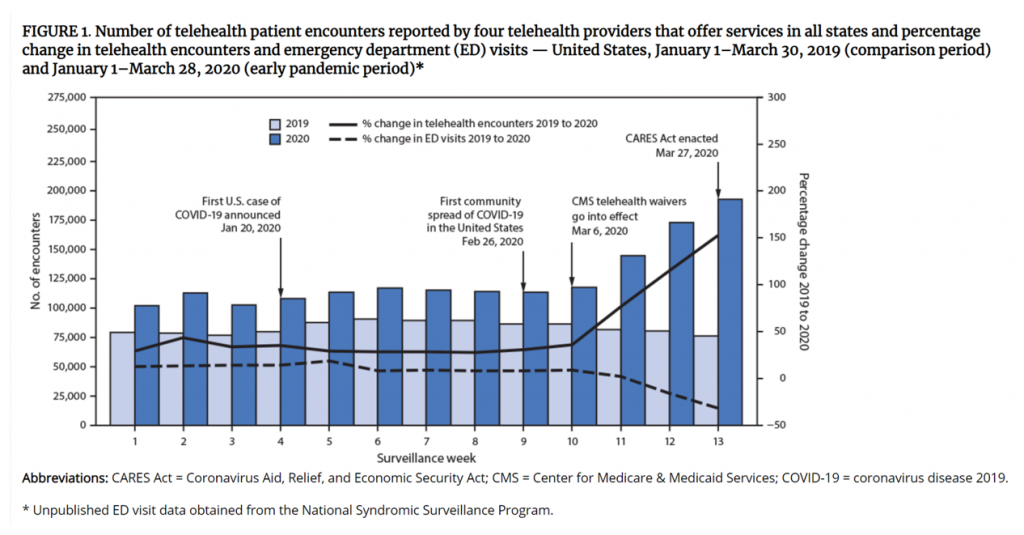

For telehealth, that S-curve has had a very long and fairly flat front-end of the “S” followed by a hockey stick trajectory in March and April 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic was an exogenous shock to in-person health care delivery. The first chart from the CDC illustrates that dramatic growth in the use of telehealth ratcheting up since the first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in the U.S.

For telehealth, that S-curve has had a very long and fairly flat front-end of the “S” followed by a hockey stick trajectory in March and April 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic was an exogenous shock to in-person health care delivery. The first chart from the CDC illustrates that dramatic growth in the use of telehealth ratcheting up since the first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in the U.S.

Virtual care has touched most families around the world, and providers quickly pivoted work-flows to the phone, to broadband, to portals, across the continuum-of-care beyond emergent care, urgent care, and dermatology. The World Economic Forum called telehealth a “game changer” for health care in August 2020.

Over a year since the pandemic emerged in the U.S., the supply side of care providers, the demand side of patients, consumers, and health citizens all, and the technology developers who have fast met the pandemic need for digital health front doors, all wonder: what aspects of virtual care will persist post-pandemic?

To help us think this through, just in time, the AMA has published a report on the Return on Health: Moving Beyond Dollars and Cents in Realizing the Value of Virtual Care. The study provides both templates and frameworks for understanding different value streams generated through telehealth, along with case studies of successful programs’ resilience and learnings.

To help us think this through, just in time, the AMA has published a report on the Return on Health: Moving Beyond Dollars and Cents in Realizing the Value of Virtual Care. The study provides both templates and frameworks for understanding different value streams generated through telehealth, along with case studies of successful programs’ resilience and learnings.

Those virtual care stories were based on interviews with a range of providers and industry representatives, shown in the graphic labelled “collaborators.”

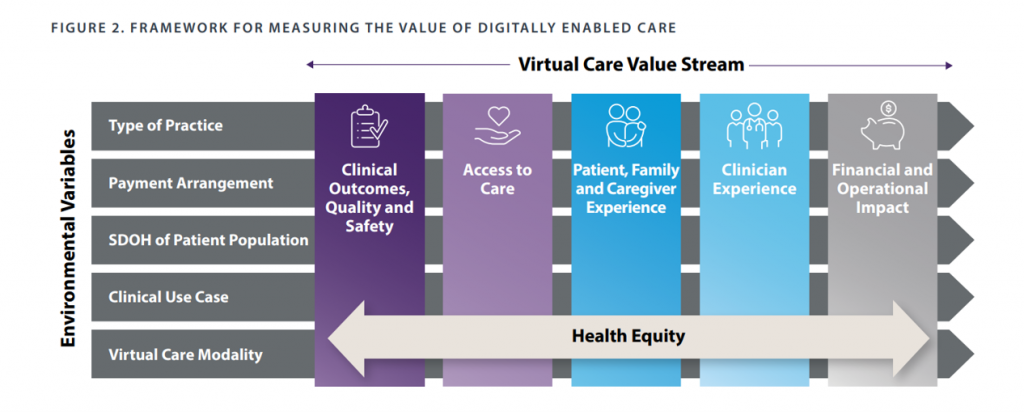

The AMA, partnering with the legal/consulting group Manatt, developed this virtual care value stream framework with five pillars of value across which health equity embeds:

The AMA, partnering with the legal/consulting group Manatt, developed this virtual care value stream framework with five pillars of value across which health equity embeds:

- Clinical outcomes, quality and safety, assessing patient mortality rates, functional status, morbidity, adverse event rates, medication adherence, patient reported outcomes, and other metrics

- Access to care, covering both availability (e.g., time to appointment and median travel time to provider) as well as equitable care (say, the percent of patients who delay care due to access barriers like lack of broadband, out-of-pocket costs, and percent of patients who lack the language to communicate with providers)

- Experience for patients, families and caregivers (such as net promoter scores patients give providers, patient activation measure (PAM) index, or HCAHPS)

- Experience for clinicians, that fourth crucial leg of the Quadruple Aim (addressing reported ease of using tech like EHRs, percent of visits conducted virtually vs in-person, or percent of physician turnover year-on-year), and

- Financial and operational impacts (which can include direct revenue, indirect revenue, direct expenses, and operational efficiencies like no-show rates and inpatient or emergency dept. throughput rates).

By putting this report out at this time, the AMA hopes to help identify opportunities for health care stakeholders to support digitally-enabled care as they, in the words of the report, “develop their coverage and payment policies and strategies in the years ahead.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I introduced this post talking about the S-curve of the diffusion of new technologies. As we consider what the next slope of that curve could look like, we should think in terms of scenario planning: considering certainties, uncertainties, and wild cards (those potential events that disrupt our forecasts and are of relatively low-probability of happening).

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I introduced this post talking about the S-curve of the diffusion of new technologies. As we consider what the next slope of that curve could look like, we should think in terms of scenario planning: considering certainties, uncertainties, and wild cards (those potential events that disrupt our forecasts and are of relatively low-probability of happening).

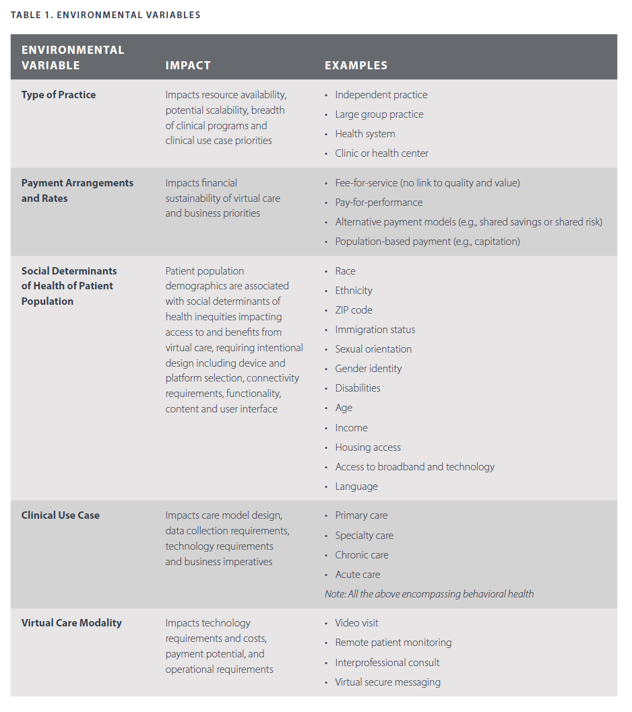

To help us in scenario planning the next several years of virtual care adoption, the report gives us the gift of identifying five categories of environmental variables; while the report presents these factors as part of the value-generated framework, several will be useful for scenario planning exercises including:

- The type of practice: independent, larger groups, health systems

- Payment arrangements and rates, from fee-for-service to pay-for-performance, shared-savings models, and other new-fangled reimbursement regimes, and,

- Social determinants of health of patient populations, dealing with health equity and barriers to care.

I would add in here new technology breakthroughs we don’t yet have at our fingertips or in the cloud, which can be wild cards in terms of, say, scaling a virtual care program. Or on the downside, a particularly onerous adverse event among a patient population or a famous celebrity which gets traction in media and/or clinical publications.

There is also legislation being promulgated both nationally and in State Houses. In the former category, you can look to the Telehealth Expansion Act as well as the more granular Ensuring Parity in MA and PACE for Audio-Only Telehealth Act. That’s public sector covered, but in your scenarios-future planning modeling, don’t leave out the commercial payors which cover another roughly half of U.S. health citizens. Some national health plans have already looked to acquire telehealth companies and embed virtual care into their models.

Look, too, to the upcoming annual 2021 ATA Conference and Expo that will bring current and futures thinking to attendees every week in June. The theme of this year’s meeting says everything the Association should be focused on at this expansive-and-uncertain moment in virtual care: “Enabling Flexible, Inclusive and Contemporary Care Delivery.”

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.