Let’s put “health” back into the U.S. health care system. That’s the mantra coming out of this week’s annual Capitol Conference convened by the National Association of Benefits and Insurance Professionals (NABIP). (FYI you might know of NABIP by its former acronym, NAHU, the National Association of Health Underwriters).

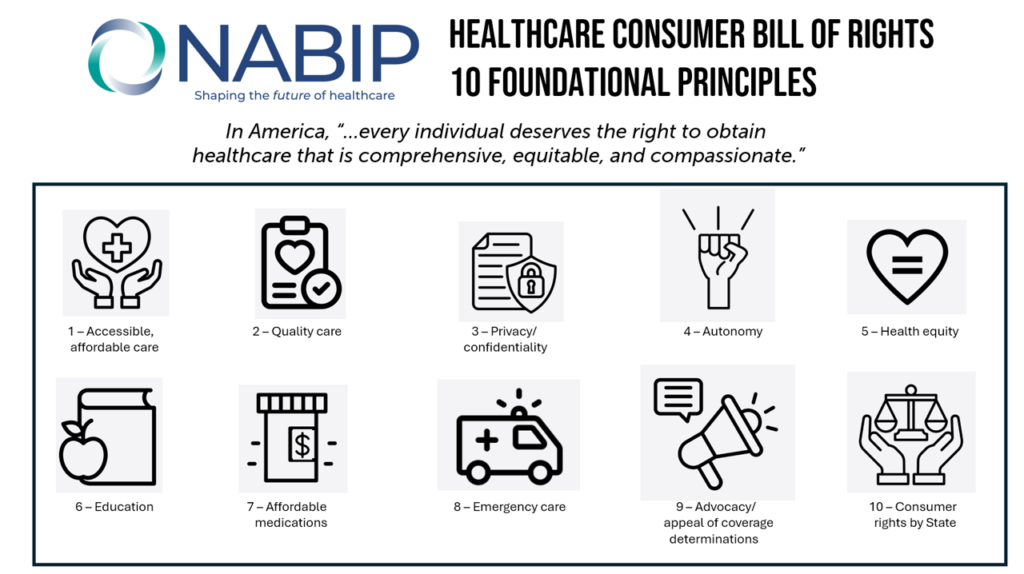

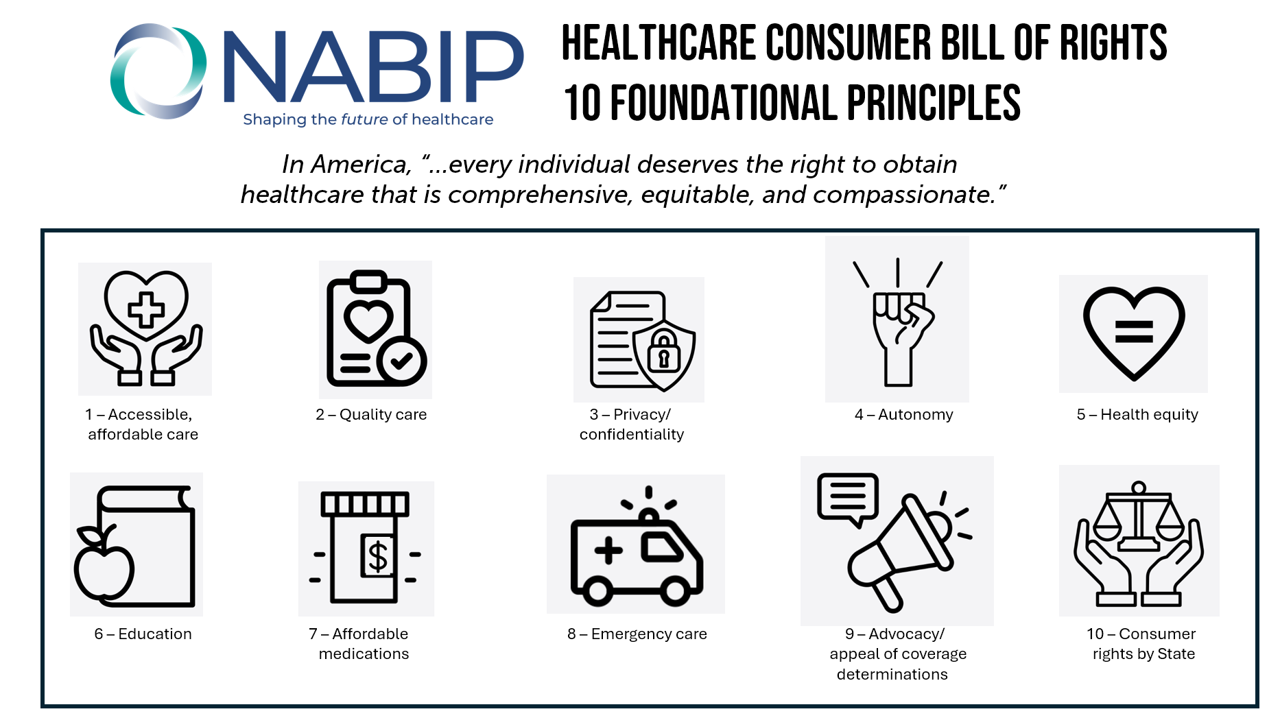

NABIP, whose members represent professionals in the health insurance benefits industry, drafted and adopted a new American Healthcare Consumer Bill of Rights launched at the meeting.

While the digital health stakeholder community is convening this week at VIVE in Los Angeles to share innovations in health tech, NABIP has assembled health insurance leaders in Washington, DC, for the 2024 Capital Conference to focus on major health reform issues that are top-of-mind for health care payors — which in today’s U.S. health economy includes employers, unions, public sector plans and other groups as well as the Consumer who now plays a role as a key payor, too — thus prompting NABIP’s American Healthcare Consumer Bill of Rights (AHCBOR).

Given the Capital Conference focus on the 118th Congress, NABIP has assembled key talking points to raise at the Federal level to strengthen health insurance for all, including supporting site-neutral payment policies, increasing price transparency, and supporting the permanent expansion of telehealth flexibilities allowed during the pandemic (specifically, encouraging the passage of the Telehealth Expansion Act of 2023).

The aspirational document sets out the mission that “every individual deserves the right to obtain health care that is comprehensive, equitable and compassionate.”

Ten foundational principles underpin health consumers’ rights in NABIP’s Bill:

Article 1: The right to access affordable health care regardless of age, gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status or pre-existing condition

Article 2: The right to quality care based on established standards of care, transparency, and clinical appropriateness

Article 3: The right to privacy and confidentiality for all health care related issues

Article 4: The right to individual autonomy, allowing each American to have the right to make informed decisions regarding their own health care

Article 5: The right to health equity, just and free from discrimination — addressing health disparities, and equal access to health care resources and services

Article 6: The right to health education to promote personal well-being and disease prevention

Article 7: The right to affordable medication, including oversight and transparency of drug prices and the promotion of generics and biosimilars

Article 8: The right to emergency care without fear of financial hardship

Article 9: The right to health care advocacy, giving each American the right to complain and pursue expedited appeal of coverage determinations

Article 10: States’ rights, enabling consumers to be able to access health care and insurance markets locally with each state charged with protecting the consumer’s rights.

In addition to highlighting the Healthcare Consumer Bill of Rights, NABIP’s keynotes and general sessions will speak to similar topics being brainstormed at VIVE this week — including mental health, maternal health, pharmacy and prescription drugs (pricing, PBMs), population health, and Medicare and Medicaid innovations.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: NABIP’s intention for ACHBOR is to re-imagine a health system “designed to serve the Consumer,” as Mark Gaunya, who reached out to me on behalf of NABIP via LinkedIn, described.

“Our collective desire is to protect the private healthcare market and create an ecosystem that treats us all like Consumers who have choices and rights,” Mark explained, making sure that I did not infer that the Association was making a political statement that health care was a “civil right.”

In fact, in the U.S., there have been many versions of so-called “patients'” as well as “consumers'” health/care bills of rights over the years. The NIH crafted one for patients enrolled in clinical trials, the American Hospital Association served one up in 1973, and many individual health providers like the University of Pennsylvania Hospital (aka Penn Medicine) have developed bills of rights for consumers entering their hospital systems.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 had embedded within the law a Patient’s Bill of Rights. Here’s a video featuring President Obama, who signed the ACA into law, discussing some of the key elements of that Bill of Rights — with an emphasis on assuring people could find health insurance even if they had pre-existing conditions, still one of the most popular aspects of the ACA (see Figures 14 and 15 in the February 2024 Kaiser Family Foundation Health Tracking Poll completed in the first week of February 2024).

NABIP’s ten-article Bill incorporates a broad range of rights that speak to today’s health care environment — with States’ rights eroding health care access for certain populations, cybersecurity threats reducing patient trust in health systems and technology ubiquity, and health disparities compromising health equity and public health across the nation.

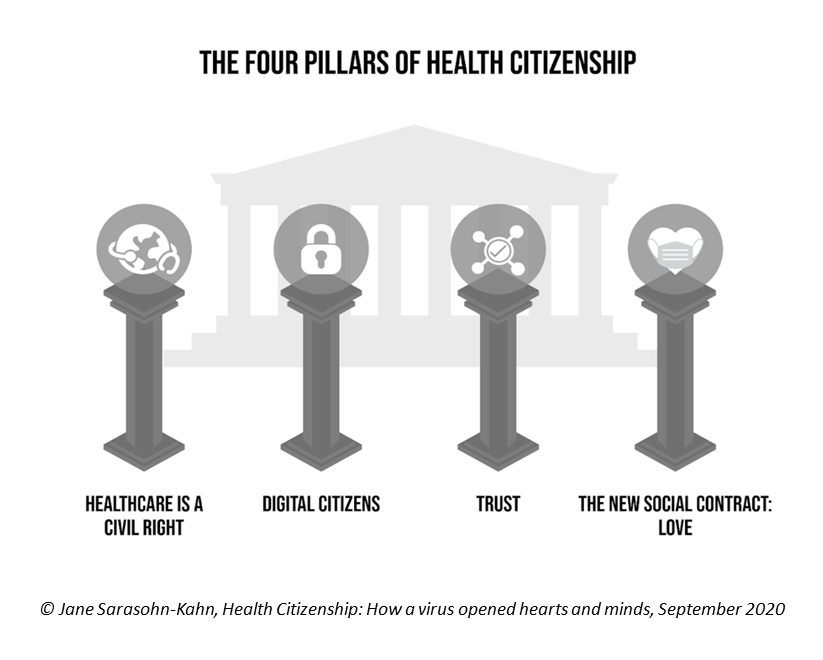

My book Health Citizenship provided this diagram of four pillars of health citizenship — with healthcare explicitly called out as a civil right, digital citizenship protecting citizens’ data privacy and control (a la the GDPR as opposed to HIPAA’s “leaky” provisions), building up trust between patients and providers, and finally the call for a new social contract — which is Love.

That Love translates, operationally and in health care law and workflows, as respect, health literacy and user-centered design principles (privacy-by-design, equity-by-design, and so on), and enabling health consumer autonomy and accessibility — that is, the right to quality, affordable care.

Kudos to NABIP for developing this document and taking a leadership position in supporting health care for all.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.