In 2020, Genentech launched its first study into health inequities. The company spelled out their rationale to undertake this research very clearly: “Through our work pursuing groundbreaking science and developing medicines for people with life-threatening diseases, we consistently witness an underrepresentation of non-white patients in clinical research. We have understood inequities and disproportionate enrollment in clinical trials existed, but nowhere could we find if patients of color had been directly asked: ‘why?’

So, we undertook a landmark study to elevate the perspectives of these medically disenfranchised individuals and reveal how this long-standing inequity impacts their relationships with the healthcare system as a whole.”

To give voice to these important perspectives, we interviewed 2,207 patients — 1,001 from the general population and 1,206 who qualified as “medically disenfranchised” from four communities: Black, Latinx, LGBTQ+, and low socioeconomic status.

To give voice to these important perspectives, we interviewed 2,207 patients — 1,001 from the general population and 1,206 who qualified as “medically disenfranchised” from four communities: Black, Latinx, LGBTQ+, and low socioeconomic status.

They found that,

- Patients do not believe that all are treated fairly and equally in healthcare

- Medically disenfranchised patients believe the system is not just flawed — but that it is actively “out to get them”

- Medically disenfranchised patients are delaying and discontinuing routine care because they do not feel understood, as the first graphic shows

- Medically disenfranchised patients are not participating in clinical trials, vaccinations, and testing due to lack of trust.

Trust is the killer app for health engagement: some 1 in 3 medically disenfranchised patients don’t participate in clinical trials, don’t get vaccinated, and don’t get tested for medical conditions due to lack of trust.

Based on these findings, Genentech concluded…

We must build bridges to medically disenfranchised patients to make them feel valued, respected, and understood. We must give them reasons to believe in the healthcare system.

We must build bridges to medically disenfranchised patients to make them feel valued, respected, and understood. We must give them reasons to believe in the healthcare system.

This year Genentech followed up the 2020 exploration of patients’ perspectives, adding in the health care provider/physician view on health equity.

This time around for the 2021 research into health equity, Genentech polled 2,200 U.S. patients online including 1,000 from the general population and 2,000 who identified as medically disenfranchised as well as belonging to one of four groups: Black, Latinx, LGBTQ+, and low socioeconomic status.

Furthermore, Genentech added health care providers into the study subject mix: they polled 403 HCPs covering physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and physician assistants.

Key findings in this year’s 2021 study were that:

Key findings in this year’s 2021 study were that:- Inequities within the U.S. healthcare system persist and are deepening for medically disenfranchised patients (still, over one-half of medically disenfranchised patients believe the system is rigged against them and worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic)

- Healthcare providers agree that the system is not serving patients as it should as one-half of HCPs said the healthcare system works in society’s best interest; 9 in 10 have seen patients quitting care

- Healthcare providers and patients agree: a positive, trusting relationship with a patient’s healthcare provider is of the utmost importance in building trust in the system overall

- There are gaps between intention and perception in the patient-provider relationship: patients and HCPs are not aligned in their belief that clinicians are sensitive to their patients’ emotions and feelings. One in 2 medically disenfranchised patients said they stopped seeking healthcare because they didn’t think their HCP understood them or would really help them. One-half of these patients also were fearful that if they asked questions of their HCP, they would look unintelligent (Genentech’s word) in front of the clinician

- Healthcare providers believe misinformation is exacerbating distrust in the system and poses a greater threat to medically disenfranchised patients.

Most HCPs believe health misinformation is a serious threat to the healthcare system and especially to their medically disenfranchised patients.

Taking all of the 2021 findings together, Genentech deduced that,

Ensuring HCPs have the support, incentives and time to build meaningful, empathetic and culturally responsive relationships requires change at multiple levels — and likely cannot be solved with training alone, or without the input of patients themselves.

Furthermore,

We are also keenly aware that we must not overestimate the opportunity to advance health equity through the patient-provider relationship without other meaningful efforts to address social determinants of health, healthcare access, cost, accountability, quality and efficiency.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Genentech joins with a growing community of public, for-profit companies calling out the reality of health and wealth inequities, and looking to be part of collaborations to address and ameliorate the disparities.

The last statement I quote just above the Hot Points speaks to the importance of some root issues over which Genentech does not have direct control — most obviously, those social determinants of health risks that can limit a person’s ability to flourish in life — from education opportunities to lack of transportation, poor environment (air, water), and adverse childhood events that echo throughout one’s life-span.

To that end, some commercial enterprises have formed the Black Community Innovation Coalition including Accenture, Best Buy, Genentech, Medtronic, State Farm, Target, and Walmart. The companies will work with Grand Rounds Health and Doctor on Demand (who merged earlier this year) to channel the first dedicated care concierge and health navigation platform designed to improve health equity for Black Americans. The companies are all part of EHIR, the Employer Health Innovation Roundtable coalition. Together, these companies employ about 500,000 workers who are Black.

To that end, some commercial enterprises have formed the Black Community Innovation Coalition including Accenture, Best Buy, Genentech, Medtronic, State Farm, Target, and Walmart. The companies will work with Grand Rounds Health and Doctor on Demand (who merged earlier this year) to channel the first dedicated care concierge and health navigation platform designed to improve health equity for Black Americans. The companies are all part of EHIR, the Employer Health Innovation Roundtable coalition. Together, these companies employ about 500,000 workers who are Black.

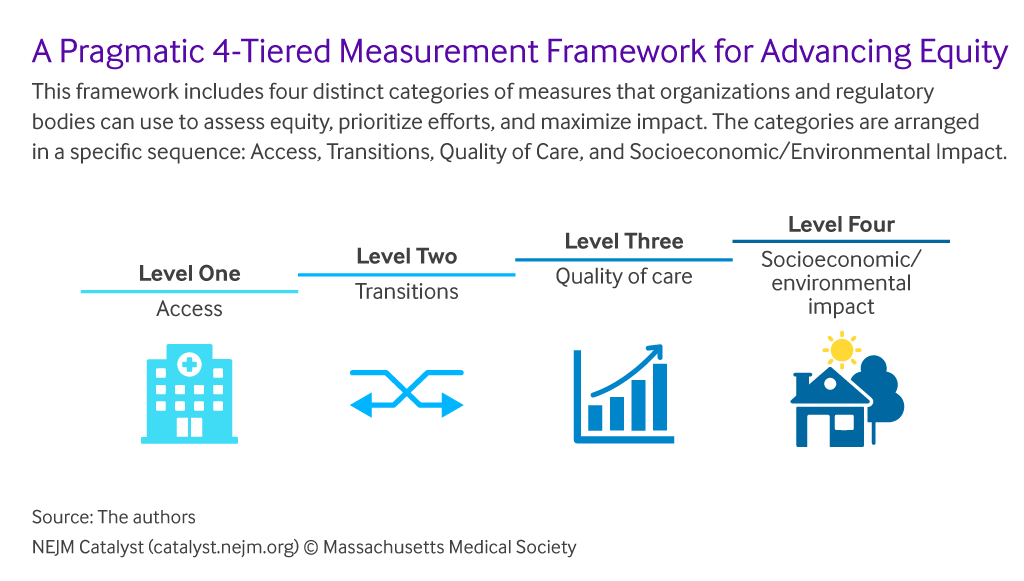

The framework shown here comes out of a New England Journal of Medicine essay on how to advance health equity across four phases. The team from Brigham & Women’s and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement notes that key limitations to this model are “a general vacuum of incentive and regulatory structures to point institutions toward a few core equity measures focused on access and transitions of care.”

The Black Community Innovation Coalition project promises to deal with some of these Level One through Level Three work-flows, to design care process and on-ramps to quality care for medically disenfranchised patients — in this instance, through the workplace employee benefit. It is possible these programs’ infrastructures could extend to larger communities, if some of the “vacuum” of incentive and regulatory structures could be broken and re-designed, too.

Ultimately, getting to that fourth level of equity — addressing socioeconomic and environmental impacts — takes an even larger village where public sector organizations responsible for the bulk of these issues — from education to clean water and minimum wage standard-setting — must be corralled into the mix.

And given that, in this moment, politics overrules rationality and social safety, we are left to private sector organizations continuing to take on public health responsibilities.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.