The following article includes contributions by Geri Lynn Baumblatt & Teresa Wagner.

Most kids grow up online. And for 70% of teens, their first source of health information is the web. It’s easier to use their phone, and they may not feel comfortable asking parents or teachers. Sometimes they do a search to find out when a sore throat may be a sign of something more serious. Other times, they want to know what medication to take for headaches, a UTI, or Plan B — or information on anxiety, depression, suicide, cutting, eating disorders, bullying, STDs, signs of alcohol poisoning, how to have safe sex, or if vaping is safe.

Also consider “time to treat” — getting accurate information so teens don’t wait to go for medical help can make a big difference in many of these time sensitive situations.

And even though teens are digital natives, it’s still hard to distinguish what information is truth versus trash. A systematic review of “Internet Use by Children and Adolescents,” by Park & Kwon (2018) found teens were confused by the information they found online about sexual health. Teens also find the information frustrating and the volume of it overwhelming. Those with lower ability to understand health information (low health literacy), rated the information as accurate more frequently compared to teens with higher ability to understand health information who knew it was inaccurate. Also, the teens with low health literacy weren’t able to say why they thought it was reliable.

Add to this, children and teens increasingly are asked to help care for ill or disabled relatives at home. Called “young caregivers,” kids ages 8 to 17 help with meals, medical tasks, bathing, and other activities of daily living. According to a national survey, back in 2005 there were already at least 1.4 million young caregivers. So, it’s clear that for their own health and their families, the ability to identify accurate online health information is essential.

A DFW Hospital Council Foundation Health Literacy Collaborative in Texas decided to tackle this issue as a part of the mission of their organization. Together with community based organizations serving teens including the Boys & Girls Club, a Children’s Medical Center, a local High School, and a Children’s Museum, the collaborative developed a workshop and toolkit called: WebLitLegit.

The workshop and toolkit created with and for teens, shows them how to distinguish science-based information from opinion, identify credible sources, question why the information exists, and analyze if it sounds too good to be true.

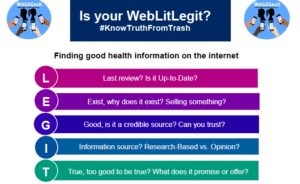

Using the acronym LEGIT, teens go through each step to test the website credibility:

In addition to pointing them toward trusted sites like the National Library of Medicine’s: Medline Plus, teens are taught to ask: Who runs or created the site? They also learn how to look at the privacy policy to figure out if they collect, share, or sell user info. Then, games like WebLitLegit Kahoot or Jeopardy help reinforce the strategies.

Although the workshop helps teens find information they may not feel comfortable asking an adult, they’re encouraged to take their findings to trusted adults (parents, guardians, etc…) since intervention and time to treat remain important. Some teens talk openly with adult workshop facilitators about their findings. This gives facilitators an opportunity to steer them towards seeking assistance from a parent or trusted adult.

The workshop has been successful in venues such as Boys & Girls Clubs, Cook Children’s Medical Center, Children’s Health Dallas, Texans Can Academy, Medical School Pipeline programs, High Schools, Fort Worth Museum of Science & History.

According to research conducted by Wagner and her team (forthcoming in the journal: Health Literacy Research and Practice1) after completing the workshop, participants expressed a high level of confidence (completely or pretty confident) in:

- Using Medline Plus (85%)

- Locating Health Information Online (82%)

- Identifying “Truth vs. Trash” (85%)

- Making Health Decisions (76%)

In addition:

- 91% would recommend the workshop to friends.

- 98% thought it was the right amount of time.

- 96% said it introduced them to at least one new health information resource they intend to use.

- 93% strongly or somewhat agreed they planned to share at least one resource they learned about.

- All reported they learned a new skill they planned to use in the future.

- 98% said it improved their ability to apply a resource they already used.

- 97% agreed it improved their ability to find useful online health information.

WebLitLegit can be implemented by almost any organization that serves teens: health and science teachers, school or public librarians, school nurses, museum educators, and community volunteers. And as we’ve seen through the pandemic, helping people recognize accurate, up to date, and reliable resources can make all the difference in health literacy, confidence, and participation in staying safe and healthy.

Notes and Resources:

Toolkit, Resources and Handouts in English & Spanish: https://www.safercaretexas.org/weblitlegitteens/

Wagner, T., Adame, T., Lewis, B., & Howe, C.J. (Accepted, pending publication). Is your WebLitLegit? Discerning credible health information on the internet. Journal of Health Literacy and Practice.

Teresa Wagner, DrPH, MS, CPH, RD/LD, CPPS, CHWI, DipACLM, CHWC is an Assistant Professor at the University of North Texas Health Science Center in the School of Health Professions. She also serves as Clinical Executive for Health Literacy at SaferCare Texas. She established the multi-stakeholder health literacy collaborative in conjunction with the DFW Hospital Council Foundation and recently established a nonprofit called Health Literacy Texas to extend efforts across all sectors. @TravelingRD

Social media: @SaferCareTexas @HealthLitTX #hcldr #healthliteracy

I realize this article deals with a subset of medical literacy directed toward teenagers, but it still bothered me to see no mention of “cancel culture” so prevalent today — especially as regards to medical advice in general. The zinger:

… “And as we’ve seen through the pandemic, helping people recognize accurate, up-to-date, and reliable resources can make all the difference in health literacy, confidence, and participation in staying safe and healthy.”

The medical establishment has suffered greatly the last two years by going “woke”, and agreeing to suppress any information that goes against the CDC-approved narrative, which seems to place Big Pharma profits ahead of sound medical advice. And Big Tech goes along with this, suppressing access to anything that goes against the Fausi-approved narrative. The Great Barrington Declaration, America’s Frontline Doctors, Dr Robert Malone, Dr Scott Atlas, ivermectin’s success in India and Brazil — content suppressed by Google, Facebook, Twitter, et al.

So such bullets as: “Information source? Research-based or opinion?”; and “Identifying ‘Truth vs. Trash’ (85%)” … ring sort of hollow. Just as in non-medical related news sources, it’s “caveat emptor”. Most mainline sources have lost credibility, so the reader must truly fend for himself to locate sources he can trust.