We read that “70% of today’s medical decisions depend on laboratory test results,” according to the CDC. This three-part series looks at modern tests from a health IT perspective. How can we make them more accurate and delivery faster results? Which ones can we move into the home? How do we eliminate wasteful, unnecessary tests? This first article offer an overview of tests and their context.

Overview of Testing

Gerry Miller, founder and CEO of Cloudticity, classifies the value of a test by several factors:

- How easy is the test to acquire?

- How complex is the test to administer?

- How much does it cost?

- Most important: How can a test consumer interpret results and make actionable decisions based on them?

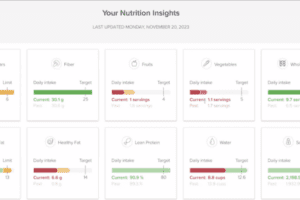

Although patient portals often display test results, the raw data means nothing to the patient. Usually, a doctor reviews the results before sharing them in order to provide the patient with an explanation, avoiding unnecessary fear and overreactions. Miller says that the doctor’s intervention is built into the workflow by most EHRs.

However, platforms such as 23andMe offer results directly to the patient.

Miller says that testing is dominated by two major players, but this isn’t necessarily bad because governments and clients become familiar with their practices.

I also heard from Dr. Yair Lewis, chief medical officer at Navina, an AI assistant for physicians. Lewis says that test results can be determined on a more personal level by using AI to analyze a patient and take into account factors such as age, sex, medical history, and even specific personalized parameters such as genomic data.

For example, a “normal” LDL cholesterol level may be defined as up to 130 mg/dL, but this range doesn’t apply to all patients. Currently, a standard distribution is used to determine the arbitrary normal thresholds. Currently, only a few lab tests have specific reference ranges, personalized to the patient; a common example is hemoglobin, which has a different reference based on sex.

Lewis thinks that in the future, analytics will track changes in lab values over time, flagging deviations from the patient’s personalized range, and prompting physicians to investigate potential causes. Personalizing the ranges can detect conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease earlier. Colon cancer screening should be personalized based on a patient’s conditions as well as family history.

Miller and Lewis expect the health care industry to integrate lab results with other data such as images, output from wearables, and genomics, to enable the long-term goal of precision medicine. (Other such measures include transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics.)

Gene sequencing and other tests are improving, but generate huge amounts of data that are hard to analyze. Lewis says that Navina’s AI tools, which use deep-learning algorithms to ingest and analyse data, are aimed at this potential market.

The Regulatory Landscape

Attorney Robert Hearn of Epstein Becker Green says that labs and tests fall under a “patchwork” of regulations. To ensure accuracy, Congress passed the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) 25 years ago. All states except New York and Washington states require adherence to the CLIA. The FDA has separate regulations for in vitro diagnostic (IVD) products, which run tests on blood or tissue.

Furthermore, state laws dictate who can order certain types of tests: For instance, to avoid the abuses created by direct-to-consumer marketing, you can’t order most clinical tests for yourself.

Not all states require licenses from labs, and those that do so enjoy the revenue they get from issuing licenses. Many states are dismantling their lab regulations because they just duplicate the CLIA or add little value.

Finally, payers have requirements, as we’ll see in the next article. Hearn would like more homogeneous regulation.

Wellness tests and tests for ancestry, such as 23andMe, are not regulated, but they can’t be used for diagnosis or to provide medical information. Hearn says that the health care industry is moving to make more tests accessible to patients directly.

New tests are usually developed in academia or by start-up companies associated with academic institutions. The big commercial labs tend to take the “bench science” and create tests around it. Getting a test approved by payers requires a big investment.

Barriers to Data Sharing

Hearn predicts that the genetic and biomarker information being collected on patients can help researchers develop new tests faster. Sharing information on patients can also improve testing in other ways that we’ll see in the next article.

Hearn worries that the integration of information from many sources will lead to problems with privacy protection and data ownership. Labs have to figure out how to seamlessly share data while preserving their proprietary interests.

Sandeep Shah, CEO of Skyscape, points to problems with interoperability, secure access, and standards. Portals don’t talk to each other, and don’t know how to authenticate people who have access to other portals.

Shah points to airport security as a model. Using an Apple device, you can get to your gate. He thinks that a big computer company such as Apple will be the one to solve the cross-site authentication problem in health care.

Skyscape’s Buzz platform provides care coordination to health care providers, offering an API for data sharing. They are creating a unified environment for patients that streamlines lab results and reports over HIPAA-secure communication channels for video, phone, SMS, and email, and they would like to work with labs too. As a transitional technology, Buzz can create a PDF and send it as a fax, and use optical character recognition (OCR) on faxes they receive.

This finishes my survey of testing. In subsequent articles in this series, we’ll look at how IT companies are improving the accuracy or usefulness of tests.