What better time to ponder the flu than during a winter plane trip, sitting next to a hipster 20-year-old you’ve never met coughing and sleeping on your shoulder? At least I had an aisle seat. And New Year’s with my new nephew and family was super-fun. And I have Purell — lots of Purell.

Anyways, it is that time of year, and according to the CDC it’s starting to look pretty ugly here in the USA. The key challenge seems to be that the annual vaccine isn’t working as well as it typically does. This isn’t a reason not to get a shot (it still appears at least 40-50% effective), but it is interesting. We create the Northern Hemisphere’s vaccine cocktail each year by analyzing what happened during our summer in the Southern Hemisphere. Unfortunately, one “flavor” of the flu has mutated too much since then — antibodies generated from H3N2 in the vaccine can’t fight off the strain that’s now in the wild.

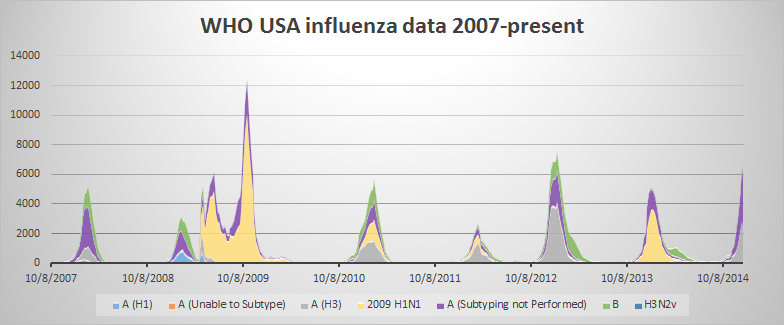

Our ongoing war with Influenza is pretty amazing, actually. There’s new drama every year as public health teams try to keep ahead of a diverse and rapidly-changing enemy. My first exposure to the cycle was during the “swine flu” freakout in 2009-2010, when we worked with Emory to build tools to help people assess the best course of action for their families. But only now through my work at Adaptive am I starting to really grok the mechanics of what is going on.

Not surprisingly, it’s all about receptors again. A bunch of spiky receptors stick out from each flu “virion” (the cool name for a unit of virus). About 80% of them are hemagglutinin (“HA”), which has the job of binding to and breaking into the host cell where it can reproduce. The remaining 20% are neuramindase (“NA”), which helps it break back out of the cell to expand the infection. ***

There’s pretty much a perfect storm of factors making the flu so successful:

- HA binds to cells that express sialic acid — which is a whole ton of our cells, especially in the respiratory system . So no matter how it enters your body, it’s likely to find a match.

- As an RNA virus, flu mutates more quickly than our DNA can — so it has an advantage in the evolutionary arms race (this mutation-based evolution is called “antigenic drift”).

- A host that contracts two flu strains at once can easily end up producing a brand new combination of H and N thanks to genetic reassortment… this “antigenic shift” is much more dramatic that drift and typically is the cause of pandemic events.

- The mechanisms behind the flu work in other mammals too, and while it’s unusual for viruses to “jump” between species, it does happen — so we’ve got a bunch of helpers transmitting influenza strains around the world.

Because there are so many different strains of flu (with more being created all the time), it’s hard to create a vaccine that can hit them all. You have to create the right cocktail, and you have to predict it pretty far in advance so that we can make enough to cover the population.

So what about Tamiflu? More evidence that science is pretty cool, and at the same time that we don’t know that much. Vaccination aside, we haven’t yet been successful at stopping these viruses once they get inside the body. But remember the “NA” side of the equation! Neuramindase enables manufactured flu virions to escape the host cell they were created in, so they can move around the body and infect more cells. Tamiflu and its ilk inhibit the action of neuramindase, which limits just how much the infections can grow before our adaptive immune system finally catches up — shortening the duration and reducing the severity of symptoms. Cool stuff. It feels a little lame to be running along behind the virus trying to slow it down, but I’ll take it over nothing! The WHO tracks effectiveness of these NA inhibitors with various strains so that we can use them optimally.

I’m not sure yet if learning these details makes me more or less of a germophobe! But the complexity of the system is amazing, and I’m proud to be going into 2015 fighting for the good guys. Bottom line — get your shot, wash your hands, and stay home if you get sick. Always comes back to the basics.

Take care!

*** As an aside, the “H” and “N” here are why we call strains “H1N1”, “H3N2”, and so on. There’s something like eighteen basic classes of hemagglutinin (three that impact humans), and nine for neuramindase. But like all things in immunology, it’s not that simple. Even with the same H and N, strains can act very differently — for example, our current “2009” version of H1N1 is fundamentally different from the H1N1 that had come before, so nobody was ready for it. There’s a whole international classification convention for this stuff.