Trust, or really lack thereof, is a killer app for people’s coronavirus health outcomes.

That is the through-line found in a very deep dive into 177 countries’ health data published in The Lancet in a research article on pandemic preparedness and COVID-19.

The Lancet study, published on 1 February 2022, was funded by the Gates Foundation in partnership with The Bloomberg Philanthropies et al. The study was researched and written up by a team of COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators, led by Dr. Joseph Dieleman of the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, a group that has been long-tracking the coronavirus since its emergence. The team analyzed data from January 1 2020 to September 30 2021.

Among over 24 data correlates the study mashed up were pneumonia relative risk, patient age, altitude (percent of population living below 100m), air pollution, smoking prevalence, cancer prevalence, COPD prevalence, bats (average number of the host bat species in a given location, GDP per capita, BMI, health spending per capita, the Gini-coefficient (a measure of income inequality, and citizens’ trust levels (based on Gallup’s World Poll and the World Values Survey), among other factors.

“These results support previous research that has found an association between trust and compliance with public health guidance,” the authors assert. “When a virus emerges with high potential for spread, governments must be able to convince citizens to adopt essential public health measures.” These measures require behavior change — like wearing masks and keeping at physical distances from other people.

“Collectively,” the article notes, “trust among people and in their government can change behaviour such that if people respond to directives and take protective health measures, they might e4xpect other members of the community to do the same.”

The New York Times featured a data-rich analysis on 1 February comparing the United States’ coronavirus death rates with other countries. A chart on risk factors for severe COVID-19 complications was part of the story, showing that the U.S. ranked first in the share of population not fully vaccinated in the context of 10 high-income countries.

The New York Times featured a data-rich analysis on 1 February comparing the United States’ coronavirus death rates with other countries. A chart on risk factors for severe COVID-19 complications was part of the story, showing that the U.S. ranked first in the share of population not fully vaccinated in the context of 10 high-income countries.

The NY Times also called out America’s higher risks for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity and diabetes, which have been found to be a risk factor for severe COVID-19 complications.

The NY Times also pointed out that deaths from future coronavirus waves would depend on the next variants of the virus, “as well as what level of death Americans decide is tolerable.”

“We’ve normalized a very high death toll in the U.S.,” said Anne Sosin, who studies health equity at Dartmouth. “If we want to declare the end of the pandemic right now, what we’re doing is normalizing a very high rate of death.”

The Financial Times covered the Lancet research, calling out noting that overall, Nordic and East Asian nations with high levels of trust outperformed countries with lower levels of confidence in their government and public health authorities (adjusting for population age).

The Financial Times covered the Lancet research, calling out noting that overall, Nordic and East Asian nations with high levels of trust outperformed countries with lower levels of confidence in their government and public health authorities (adjusting for population age).

“Argentina and the US, which have less trust in their leaders, had greater numbers of infections per capita than many other high income countries.”

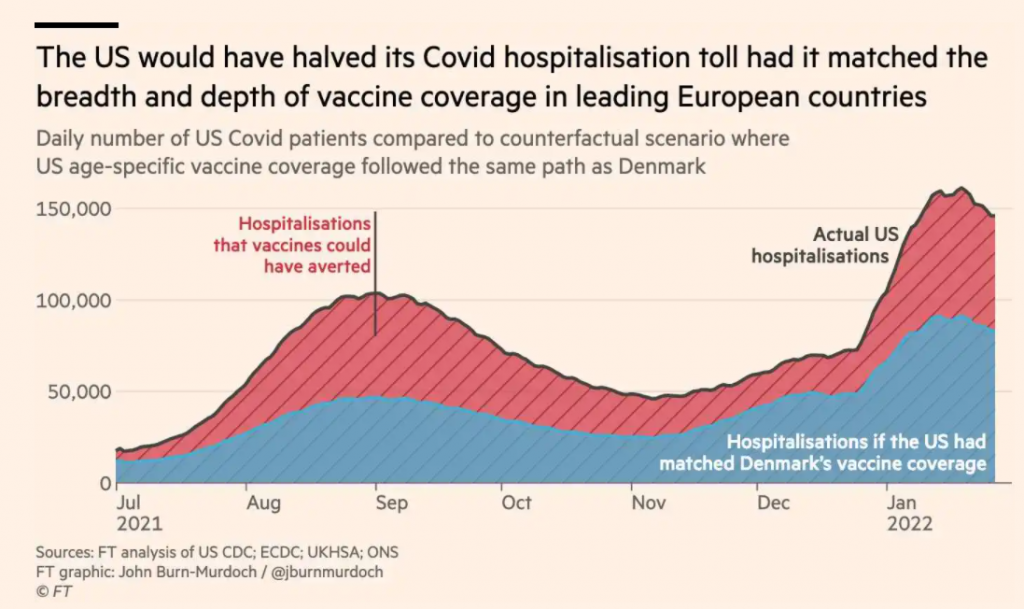

The FT also dove deeper into one of the Lancet’s discussion points on Denmark, shown in the chart here. If every nation trusted their government to the level of Denmark, which was at the 75th percentile on trust, then global COVID-19 infections would have been 13% lower, the FT calculated.

The graph illustrates where the U.S. would have been were Americans to replicate the Danes’ example.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Trust is the prescription when it comes to a nation’s ability to achieve low COVID infection rates, based on The Lancet analysis.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Trust is the prescription when it comes to a nation’s ability to achieve low COVID infection rates, based on The Lancet analysis.

“The outsized role of interpersonal trust in this pandemic is unsurprising,” The Lancet research concluded.

Fortunately, trust is something that can be fostered, even in a crisis,” the authors optimistically wrote.

“Trust is a shared resource that enables networks of people to do collectively what individual actors cannot,” The Lancet piece cited a classic article I had read nearly 20 years ago on “Health by Association,” akin to the more recent seminal work on social networks and health, Connected by Christakis and Fowler.

Thus is my call-to-action for health citizenship — to take on the individual responsibility to “do collectively what individual actors cannot,” as The Lancet coined.

Thus is my call-to-action for health citizenship — to take on the individual responsibility to “do collectively what individual actors cannot,” as The Lancet coined.

As we muddle through the pandemic in America, I am also living and working in Brussels, Belgium, where the vast majority of health citizens are masking in public, on trams and subways, in retail shops and grocery stores, required to show our QR-coded vaccination status to enter a restaurant or museum or health club.

Health citizenship is all of this, and more. Bottom-line, it’s a social contract we have with each other where we land on trust and loving-thy/our-neighbors for the benefit of all.

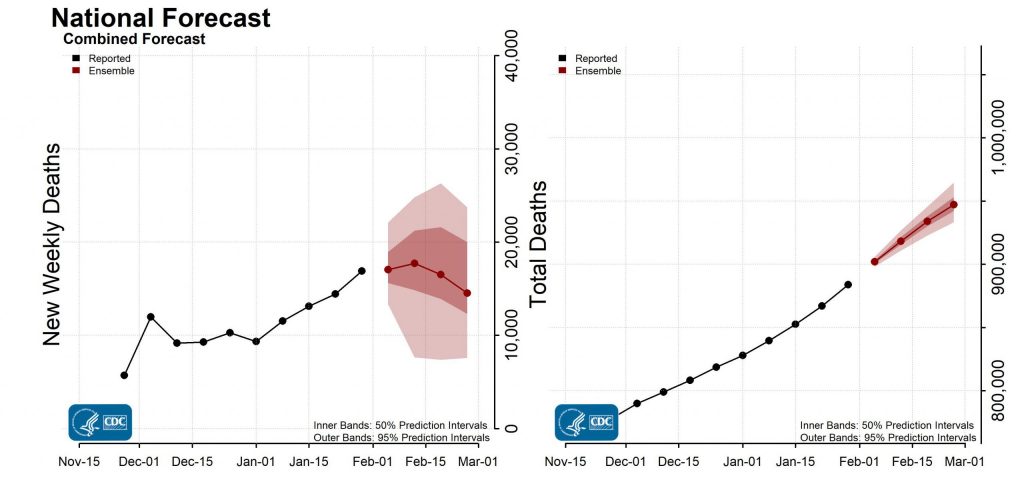

And if that wouldn’t be enough to convince the health citizen naysayer, perhaps the prospect of nearly 1 million deaths in the U.S. due to COVID-19 forecasted by the CDC would be.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.