One of the major complaints about new digital technologies that clinicians have made over the past decade is the disconnect between the application created by the developer and the daily workflow of the users. It has taken a long time for developers, drenched in technology’s potential, to learn to work with the people who must ultimately use their products and services. A promising model is offered by Lifelink, which embodies user workflows into chatbots.

I recently chatted with Greg Johnsen, CEO of LifeLink. He said that their solution involves AI for both the natural language processing (NLP) required by chatbots, and for automating patient-facing workflows before, during, and after healthcare visits. It’s important to know that LifeLink does much more than develop the underlying technology that powers these workflows; it also works intensively with each customer to configure and fit its workflows, meeting the unique requirements of each organization.

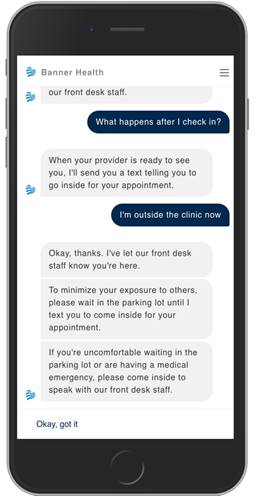

One example of the kind of workflow LifeLink automates is what it calls the Virtual Waiting Room, which rolled out at Banner Health and Memorial Health System. Instead of waiting in the waiting room and completing all the paperwork and registration process there, a patient interacts with a chatbot that reaches out days before the visit to remind and educate the patient. The chatbot gets them started on their registration and paperwork with personalized chat-based interactions on their mobile phones. Patients fill out all required forms in advance, from the safety of their homes, Then, when it’s time for their visit, the chatbot directs them, keeps them updated, and lets them know when the clinic is ready to see them, so they can bypass the waiting room altogether.

The chatbot interaction starts with a privacy and security check, making sure you’re really the person who was supposed to get the message. Drawing on information from your health record, the chatbot asks you for a couple key pieces of personal information, such as birthdate. Because ease of use needs to be balanced with security, each clinic can configure how many questions to ask and how often to re-authenticate the user over time.

You now get an intake form designed by the clinic. You can fill it out at any time convenient for you and save an unfinished form to fill out later. If you forget to fill out part, you are prompted to finish it before your appointment. Furthermore, the chatbot can answer basic questions such as how to get to the site, and help you change the appointment if necessary.

You get more reminders as the time of the appointment comes close and are asked to wait outside the clinic because of COVID-19 restrictions. When the moment comes for you to enter, you are prompted by the chatbot. All the information you put on the form has been uploaded to the clinic’s EHR and scheduling system, so you don’t have to sit in a waiting room, but just come in at the right time and announce yourself to the receptionist.

This scenario, typical of a LifeLink deployment, shows the need for extensive research and coordination. The clinic’s policies and workflows have to be embodied in the directions given to the patient. Information must be transferred between separate systems. The chatbot must be able to anticipate patient questions and needs.

Numerous advantages spring from doing this research and integration

- Patients have information at their fingertips any time of the night and day. Whereas they might feel intimidated at asking a lot of questions to a busy clinician, they can ask the chatbot all the questions they want. The availability of information makes them feel less anxious about the procedure, and therefore more likely to show up.

- A huge amount of staff time is saved, enabling them to focus on clinical needs instead of patient communications and logistics. Johnsen mentioned one particular benefit that might have gone unnoticed: chatbots can handle clerical work with patients after-hours when clinical staff may not be available, helping to complete forms, answer questions, and prepare patients for appointments.

One of the conversational components that LifeLink has developed, tested and deployed is a screener: an interactive clinical questionnaire. For instance, they now offer every clinical setting a COVID-19 screener that asks questions and triages a patient. The same principle can apply to depression and other common conditions.

A key feature of LifeLink is the use of analytics to determine when to trigger a screener. Analytics can help the app determine the most likely intent of the patient at each step and present the patient with the most likely options.

One screener can also trigger another, and the triggers can cross boundaries–for instance to store patient information in an EHR. Naturally, the information automatically inserted into the EHR is more likely to be accurate, to be coded instead of free-form, and to enter the right fields. EHR integration nowadays is easy, Johnsen says; the main barrier is getting attention from the IT staff to do it.

LifeLink supports multiple languages. A lot of their analytics and workflow analysis don’t depend on language, but they can also use NLP to analyze text, such as transcripts of call sessions. Where the organization lacks that kind of pre-existing information, some time might be spent collecting data for the analytics.

Some sites have strict, regulated workflows: for instance, what a call center operator can ask and tell a patient. Even in these situations, LifeLink can uncover unusual or unaddressed patient interactions, and make the workflows more flexible and realistic, according to Johnsen.

LifeLink offers services to many healthcare organizations: not just clinical ones, but also researchers and life science companies. Like Lumeon, another company whose workflow services I have covered in this publication, LifeLlink seems to me a very responsive company, alert to client needs. Their consulting approach is labor-intensive, but the results seem to reward the investment several-fold.