OK, everyone, raise your hand if you’ve gotten wrong information when you’ve looked up a clinician on your insurer’s web site. I don’t think anyone will have both hands on the keyboard right now. According to a Medicare research study, for instance, the information about nearly 49% of the providers in Medicare Advantage Organizations have at least one inaccuracy.

Put your hands down and read on to see how one company named H1 is fixing most of the errors, and making a bundle of money along the way. This article is based on an interview with Ariel Katz, founder and CEO of H1.

Why So Many Errors Creep Into Insurer Databases

From a consumer viewpoint, it seems strange that insurers display so much wrong information about something so basic as the providers they cover. When the insurer lists a doctor who has retired, or an address that the clinic left six years ago, or some other glaring error, it’s like an auto dealer who claims to sell Chevrolets when all they have is Subarus.

Any computer professional can tell you the right way to fix this information gap: create a standard data format for all public information about providers, and ensure that any time the office staff update their internal database, the change is propagated in milliseconds to all the payers. This solution is not in the cards.

So what do clinicians and payers do currently to create provider databases? According to Katz, the problem is like most sources of erroneous business information: transcription errors caused by manual processes. Some staff member is responsible for making a list of changes every month and sending a roster of doctors to each of the payers who cover the organization. There is no way to draw this information automatically from the organization’s digital records. So naturally, errors enter.

The situation gets even more absurd on the payer side. Knowing that the information is often incorrect—this is not something to which payers are indifferent—the payers devote hundreds of staff people to phoning clinicians and asking for updates. This leads to some corrections and a lot of errors on either side of the conversation. But 2.1 billion dollars a year is spent on this exercise, which could as well be taking place in the nineteenth century.

Katz says that problems with accuracy are even worse outside the United States, where providers and payers have less money to throw at the problem. But this article focuses on the United States, because that makes it easier to focus on details of the solution.

Curating Data About Health Care Providers

In the absence of true digital synchronization, there is another solution. It involves a huge investment of time and intelligent data analysis, culling data from hundreds of sources. But H1 has made it work.

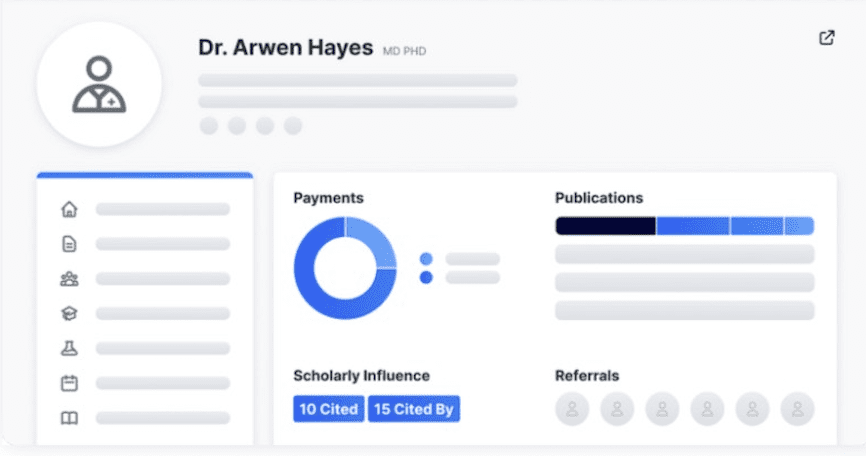

A look at a display from H1’s Precise can be stunning (Figure 1). Not only do you get contact information and other basics about the practice—you can see a full profile of the doctor, such as languages they speak and the races of people they treat (very important for finding a doctor who is compatible with you), publications, awards, affiliations—even what procedures they’re rated highly for.

In short, H1 makes public what had previously been hidden, or buried deep in a thousand hard-to-reach places.

Some of the data sources are indeed public, whereas H1 gets others through partnerships with payers. H1 offers the information on tens of thousands of providers around the world.

They spent about 171 million dollars over seven years to gather, check, and organize their data. The database is vastly larger, richer, and more accurate than the directories on which the insurers have been spending 2.1 billion dollars a year.

Analytics play a crucial role in automating checks. For instance, checking publications and credentials runs into the same problems providers have ensuring patient identities. Like the algorithms that identify patients, H1 uses many criteria to make sure that credentials attributed to Lakshmi Subramanian (two common names) are associated with the right doctor.

Building a Business on Accurate Data

H1 didn’t start with insurers as clients. The company’s first clients were in pharma and related research. The databases were useful to them for a slew of reasons: to find subjects for clinical trials, identify promising candidates for research funding, and more.

The market among payers appeared after the U.S. Congress passed the “No surprises” act. Among other things, it penalizes a payer $10,000 for each clinician it lists with inaccurate information. For large insurers, who might list a million providers around the country, the act provided a sudden incentive to improve their game. (The sudden prioritization of accuracy is comparable to the effect that Medicare’s “30-day” rule had on hospitals, even though the rule’s efficacy and fairness have been criticized. Suddenly, the hospitals had an incentive to keep patients from relapsing after discharge.)

Thus, H1’s entry into the payer market was unplanned, almost opportunistic. But payers are signing up in droves. Although H1 cannot promise correct information—the liability still lies on the payer—the company has found that their data is 95% accurate.

Sitting on a database of this size, which would be so hard to reproduce, gives H1 a lot of power. I asked whether there are limitations on how they use the data. Katz said that some of the data sets are contractually limited. For instance, some may be applied only to clinical use, not marketing. But he said the company has no reason to abuse the data. They’re doing fine financially with socially beneficial applications.

When we hear so much these days about large corporations putting data to uses of which the public disapproves, we need more stories of data collection and analysis improving everybody’s lives. It looks like H1 is a prime example in the healthcare field.