The recent turn to a more holistic health care system—such as the interest in dealing with social determinants of health, covered in a recent SDoH series on this site—places a new urgency on connecting patients to services that provide counseling, food, transportation, and other needs that affect their health.

Many people among impoverished and under-represented populations don’t use the services to which they’re entitled. The people might not realize these services exist, or don’t think they need help, or don’t think they deserve it. Many of these people enter the ecosystem of human resource organizations when they have an acute health problem, and therefore are often referred to the services by health care organizations.

And who offers these services? Child, youth and family agencies, re-entry programs from prisons, and many other nonprofits, government, and tribal agencies. These often operate off of shoestring budgets, and the vast majority are still using pen and paper records.

To see how digitization can improve workflows and efficiency, I talked to Tristan Louis, founder and CEO of Casebook, which concentrates on digital tools to help agencies dealing with impoverished and disadvantaged populations.

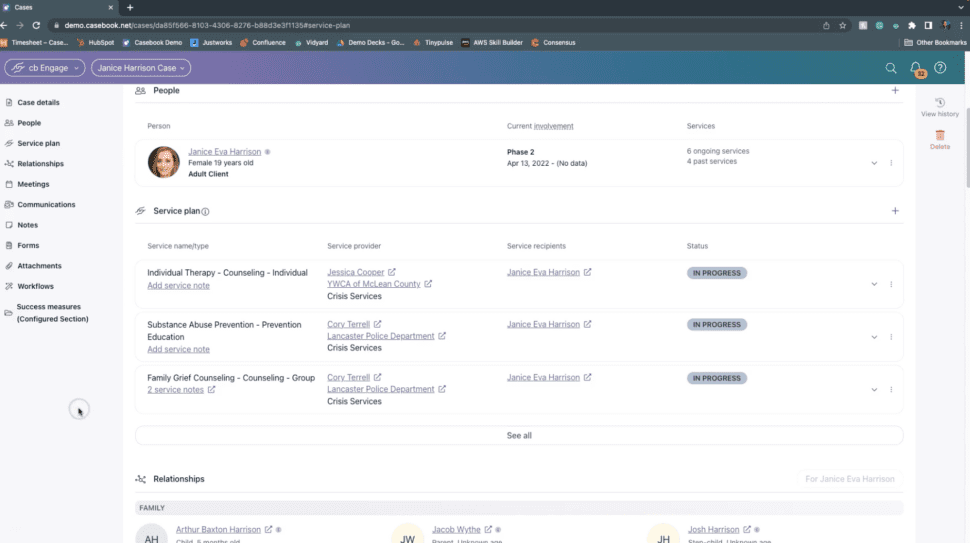

He pointed out that services are often a revolving door for their clients, who may undergo repeated contacts with the health care system as well as with the criminal justice system, housing placement, and other institutions. Typically, an agency opens a case when someone applies for help, and closes the case when the person leaves the system. Crucial information is lost when the person returns and a new case is opened.

So long as the clients can reconnect with staff who know them and their histories, the agency can search for ways to build on their experience and do things better each time. But staff move on to other jobs, or turn cases over to colleagues because everybody is chronically overworked, or just don’t have the mental bandwidth to look over the record.

Thus, digitization and the assignment of persistent patient identities are the first steps to a learning system. Figure 1 shows a typical service plan.

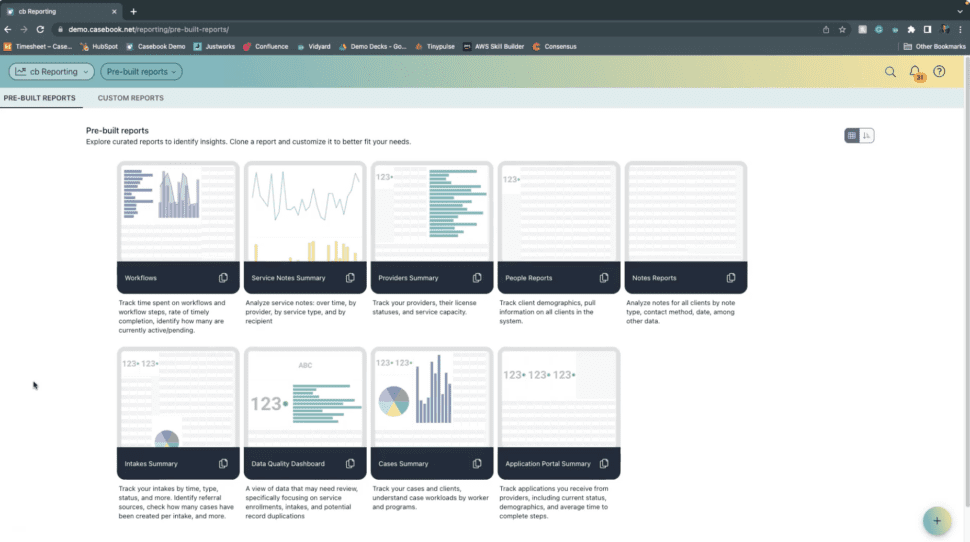

Although Casebook doesn’t have enough data yet to do predictive analytics (Louis warns that “you can wreck a life” if a predictive model makes mistakes), they are expanding their clientele with the goal of accumulating enough data to start making their tools more helpful. Figure 2 shows some current reports Casebook can generate.

Louis says that their workflow tools and data model is based on millions of pages of government regulations related to social services data. Business logic is layered on top of the data model and the company’s proprietary API. The tools support customization, such as the ability to create forms, new data elements, workflows, and reports that are tailored to the unique needs of a given agency.

Casebook can integrate with the electronic health records at a healthcare site. For example, when the clinicians request a service such as transportation, Casebook can record the steps it takes to carry out the request (order a ride share, remind the patient, etc.) and notify the clinician about the outcome of the request.

I asked about computer and Internet access in rural and impoverished areas. Louis said these used to be big problems, but the intense build-out of networks during the COVID-19 pandemic means that nearly every geographic area of the U.S. has passable Internet access. The Casebook PBC platform works on desktop computers and mobile devices, with apps for caseworkers who are using mobile phones on the move and might have to go offline.

Casebook can be tailored to serve the specific needs of tribes and First Nations, a segment that has historically been under-served. (This point is particularly worth noting now because November is celebrated by many U.S. agencies as National American Indian Heritage Month.)

At this early stage, Casebook measures process indicators such as engagement or time savings. Eventually, longitudinal data will reveal the tools’ impact on the health of the populations served.

As an example of a program’s success, digitization saves one organization 20 hours of clerical labor per week, allowing them to spend more time with clients and increase their impact.

We must remember that the big push to digital records launched by the HITECH act in 2009 gave billions of dollars to clinicians but didn’t reach the social service agencies that we now depend on for social determinants of health. Thus, the agencies have been trying to evolve and adopt 21st-century tools with little support. A true, thorough-going interest in improving patient lives holistically should integrate the many agencies served by Casebook with our modernizing health care systems.