The hearts and minds of nurses are fertile and inspirational sources and engines for health care innovation.

This past weekend, and for the second time, I had the privilege and opportunity to be a panelist for the perennial hackathon meet-up of Nurse Hack 4 Health, sponsored by Microsoft, Johnson & Johnson, Sonsiel, and DevUp.

This round, the hackathon attracted hundreds of nurses from at least 20 countries and 30 U.S. states. Even a few students attended, a growing trend as academia recognizes the shortage of workers trained to solve thorny problems of the world.

In health care, right here, right now at the May 2021 #NH4H session, our problems were categorized in four challenge areas;

Vaccine education and delivery

Vaccine education and delivery- Medical Deserts

- Health equity, and

- Care settings (think: outside or away from the hospital bed or doctor’s office).

I had the pleasure of attending the pitches with three collegial peers: a Chief Nursing Officer with a national health plan; a serial entrepreneur and venture funder whose first project was inspired by his nurse-mother; and, a Chief Innovation Officer at an NGO. We brainstormed with four innovator teams in the care settings category, focusing on four quite-different health system challenges where technologies can drive positive change:

- How PPE can be better allocated, rationalized, and shared in local/regional health care markets

- How waiting times in hospital emergency departments can be shortened to lower the risks of adverse events and quality problems that can be averted by seeing patients sooner

- How health care providers’ mental health and wellbeing have eroded in the pandemic, and what chatbots trained in cognitive behavioral therapy can do to address this threat to the Quadruple Aim; and,

- How patients can better control their personal health data through making data more “liquid” applying HL7 FHIR standards, QR codes, and channeling through first responders.

Each of the teams with whom we collaborated did a stellar job with their pitch desks, business model articulation, and deployment of the latest technology – for example, chatbots working toward mental health and FHIR standards toward interoperability. We also saw the use of blockchain, AI and cognitive computing, smartphones, neural networks, among other tools in the digital health toolkit.

Each of the teams with whom we collaborated did a stellar job with their pitch desks, business model articulation, and deployment of the latest technology – for example, chatbots working toward mental health and FHIR standards toward interoperability. We also saw the use of blockchain, AI and cognitive computing, smartphones, neural networks, among other tools in the digital health toolkit.

What makes a good hack, anyway? The five-section circle, offered as succinct guidance at the #NH4H event, tells us: the hack should meet a real need, be rooted in real-life stories, be scalable and iterated, and tested to identify glitches and problems that can be addressed and used to continue the iteration and ongoing improvements to the solution.

Each of the four projects our team evaluated had important stories at their core: a father’s DNR wishes not found in his moment of truth and end-of-life; patients waiting for hours in an emergency department in India, their acute conditions worsening by the minute; the isolation and despair felt among millions of clinicians dealing in COVID-units the world over; and, finding supply closets fast-emptying of masks and gowns as the pandemic swept through hospitals seeking supplies just-in-the-knick-of-time.

At this hackathon, we were all winners: we shared, we learned, we rolled up sleeves together to envision a better, more equitable, safer health/care system for our brother and sister health citizens and provider colleagues the world over.

My thanks to the organizers for inviting me into the #NH4H sandbox at this most challenging moment for health care delivery around the world.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Why support nurses for health care innovation? Among a long list of reasons I could articulate, two of my favorite rationales are that:

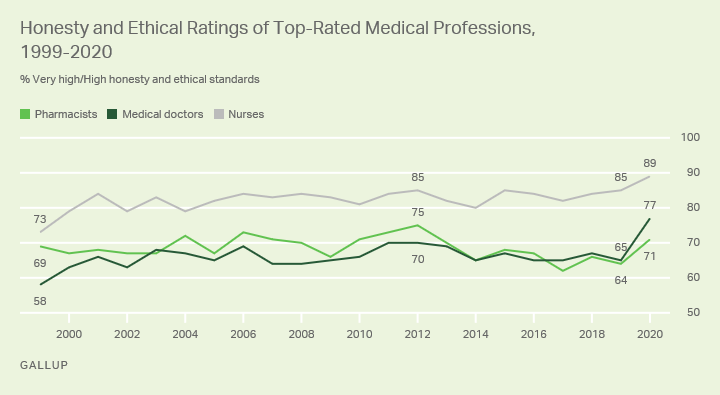

1. Nurses are the most-trusted working persona in health care; check out the Gallup Poll on Honesty and Ethics in Professions in the U.S., just one example quantifying consumers’ ongoing respect for the nursing profession above all other job types in America; and, that

2. Nurses are on the front-lines of health care, up-close-and-personal with both patients and physicians, seeing and experiencing the system’s problems first-hand and, often, quite personally.

Bolstering my two points is a book I can’t put down titled Compmassionomics: The Revolutionary Scientific Evidence That Caring Makes A Difference.

The book was written by two physicians from the Cooper University Medical Center in Camden, NJ: Dr. Stephen Trzeciak is the Chief of the Department of Medicine at Cooper, and Dr. Anthony Mazzarelli is the Co-President/CEO at the institution. Together, these two clinical leaders have observed the power that caring really does make a difference in patient outcomes and health care quality.

The book was written by two physicians from the Cooper University Medical Center in Camden, NJ: Dr. Stephen Trzeciak is the Chief of the Department of Medicine at Cooper, and Dr. Anthony Mazzarelli is the Co-President/CEO at the institution. Together, these two clinical leaders have observed the power that caring really does make a difference in patient outcomes and health care quality.

It is not common to read, say, JAMA or the New England Journal of Medicine to find heart-felt essays by physicians waxing lyrically about empathy, caring, and compassion.

These doctors do so, quantifying the impact of “compassionomics,” with the bottom-line that, in their words and arithmetic, “forty seconds of compassion can save a life.”

The book tests the hypothesis that Compassion Matters. “Specifically,” the authors write, “the hypothesis is that providing health care in a compassionate matter is more effective than providing health care without compassion by virtue of the fact that human connection can confer distinct and measurable benefits.”

The rest of the book sorts through the data-based evidence on compassion in the medical literature, which is the first time the hard data on compassion’s impact on health and health care has been published in one place, the book asserts.

With over 400 footnotes and 300+ pages of analysis, the good doctors gleaned over T1,000 scientific abstracts and 250 research papers.

The wordle shown here published in the book demonstrates that “Compassionomics” is a field that is so new there was no single search term to use for curating this research.

The wordle shown here published in the book demonstrates that “Compassionomics” is a field that is so new there was no single search term to use for curating this research.

Their bottom-line: there is no substitute for clinical excellence, full stop. But when compassion is used in conjunction with clinically excellent care, it is very powerful. It is an “and” the authors say, not “either/or.”

In addition to the physiological, psychological, and economic benefits that accrue with the addition of compassion to clinical care, the doctors also discuss compassion as an antidote to clinician burnout. “It appears that when health care providers are under the most stress,” they say, “that compassion is needed the most for their own well-being.”

Oh, and by the way: the doctors dedicated Compassionomics to, “all of the nurses we have ever worked with and that we continue to work with. Your compassion for patients has saved many a life and has inspired us to be better doctors.”

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.