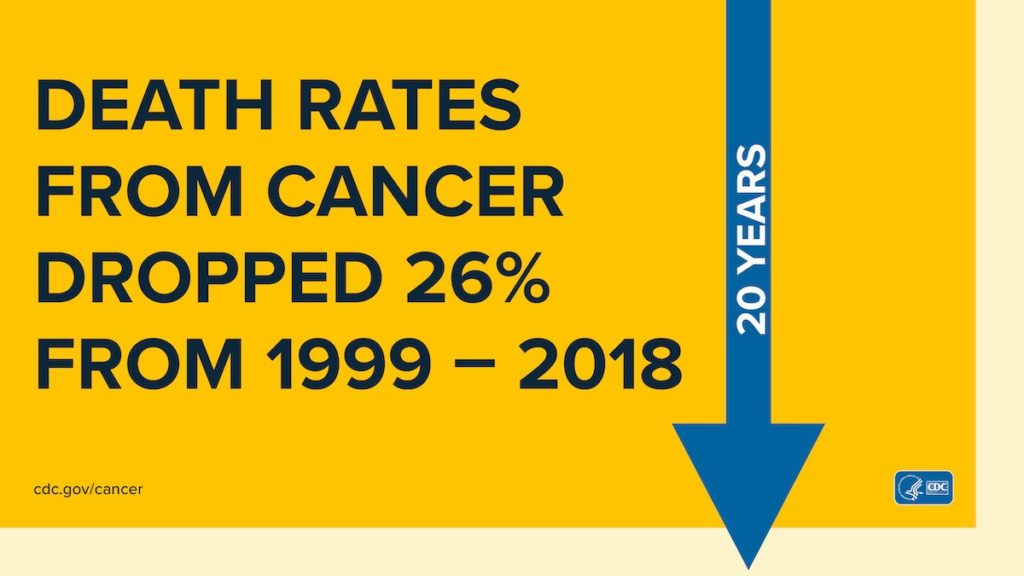

There was great news published last week in An Update on Cancer Deaths in the United States from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC): cancer mortality rates have declined by 26% over 20 years, between 1999 to 2018.

There was great news published last week in An Update on Cancer Deaths in the United States from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC): cancer mortality rates have declined by 26% over 20 years, between 1999 to 2018.

The drop in deaths from cancer in America was indeed positive during the current public health COVID-19 pandemic, a public health data story easily lost in an overwhelmingly tough week in the U.S.: still embattled with the coronavirus, the nation also continues to shed jobs with the growing threat of an economic recession and financial ill health for mainstream consumers, and the tragic death of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

These three American realities are interrelated, which I’ll weave together in this post.

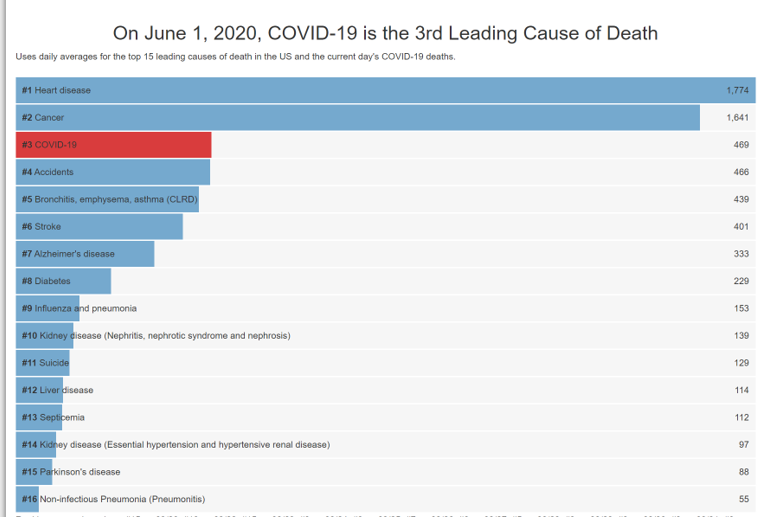

Start with the CDC story, the importance of which we should both laud and details of which, understand. Cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the United States, shown in the second chart.

Start with the CDC story, the importance of which we should both laud and details of which, understand. Cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the United States, shown in the second chart.

In 2020, there’s a new third-place cause for mortality in America: COVID-19. In 2018, there were 599,274 cancer deaths; 283,721 were among females and 315,553 among males.

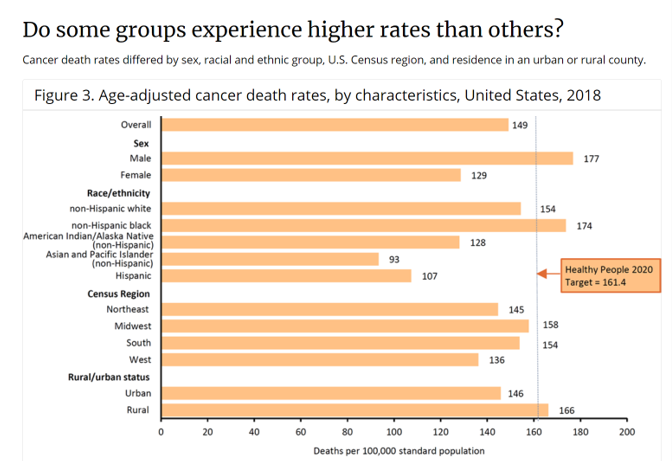

Collectively, blacks in America have the highest death rate and shortest survival of any racial/ethnic group in the U.S. for most cancers, according to The American Cancer Society’s portal that continually tracks data for black people living in the U.S.

“The causes of these inequalities are complex and reflect social and economic disparities and cultural differences that affect cancer risk,” as well as, “differences in access to high-quality health care, more [impactful] than biological differences,” the ACS explains.

Health inequities persist in the U.S. across medical conditions, mortality and morbidity, and access to services.

The rate of cancer deaths is one of these health disparities, clearly communicated in CDC’s bar chart here for age-adjusted cancer death rates by characteristics.

The death rate for all cancer types for non-Hispanic black people was 174 per 100,000 deaths in 2018, compared with 154 for non-Hispanic whites: a 13% difference between whites and blacks in America.

Note that the rate of cancer deaths for black people in the U.S. exceeds the CDC’s Healthy People 2020 target of 161.4.

The ACS compares cancer death rates between non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites, finding higher incidence and death rates for black males than white males for all cancers combined, and higher for prostate, lung, colorectal, kidney, liver, and pancreas cancers.

Non-Hispanic black women have higher death rates for cancer than white women have for breast and uterine corpus cancers — even though black women have a lower risk of cancer diagnosis than white women…but a 13% higher risk of cancer death, ACS calls out.

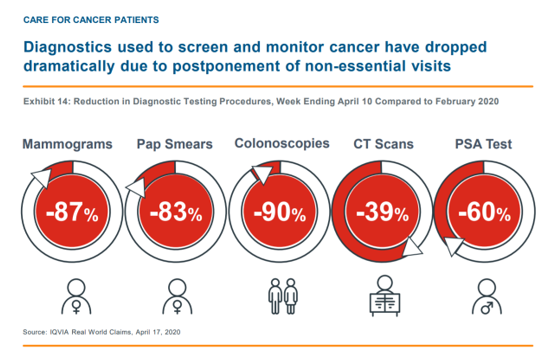

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on patients seeking care for many issues other than the coronavirus. This resulted from a combination of physicians shutting down regular office operations during the initial weeks of the pandemic shutdown, and at the same time patients’ need to reduce their risk to the infection,

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on patients seeking care for many issues other than the coronavirus. This resulted from a combination of physicians shutting down regular office operations during the initial weeks of the pandemic shutdown, and at the same time patients’ need to reduce their risk to the infection,

Oncologists’ interactions with patients declined by an average of 20% between February and April 3rd, 2020, according to IQVIA’s analysis of medical claims in the period. This varied by tumor type and cancer progression. But it’s clear from IQVIA’s data that for at least six weeks, a minimum of 5 million fewer cancer patients engaged with a prescriber, either in person or via telehealth, based on what IQVIA would have expected based on 2019 claims data.

The circle chart presents IQVIA’s claims data comparing 2020 diagnostic testing procedures for several categories with 2019 patient volumes for the same tests. We can see reductions in test volumes for three big cancer screens: mammograms (down 87%), pap smears (reduced by 83%), and colonoscopies (down 90%).

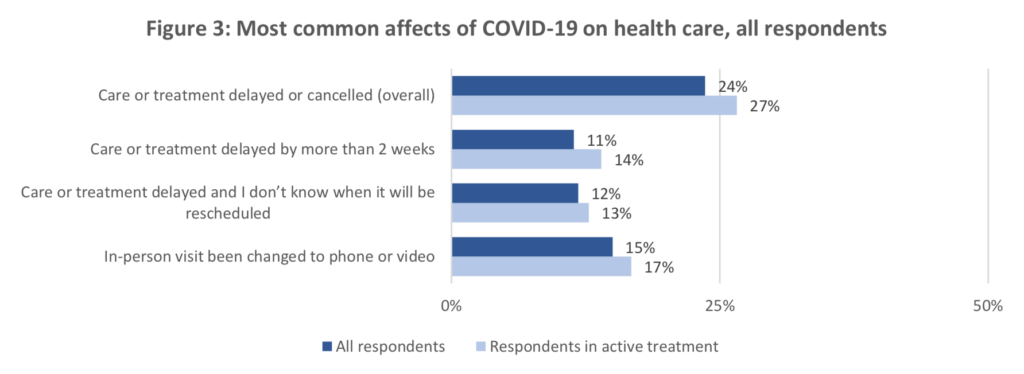

The American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network looked into cancer patients’ and survivors’ engagement with physicians and cancer-focused services in March and April 2020. One-half of these folks reported an impact to their health care due to the COVID-19 pandemic: 27% of patients in active treatment had a delay in their treatment. Furthermore, 38% of cancer patients and survivors said they had a “notable impact” to their financial situation that affected their ability to pay for their cancer care. One-third of these people were concerned about COVID’s impact on their ability to get treatment for their cancer, especially acutely felt among patients in active treatment (40% of whom were worried).

The American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network looked into cancer patients’ and survivors’ engagement with physicians and cancer-focused services in March and April 2020. One-half of these folks reported an impact to their health care due to the COVID-19 pandemic: 27% of patients in active treatment had a delay in their treatment. Furthermore, 38% of cancer patients and survivors said they had a “notable impact” to their financial situation that affected their ability to pay for their cancer care. One-third of these people were concerned about COVID’s impact on their ability to get treatment for their cancer, especially acutely felt among patients in active treatment (40% of whom were worried).

This week, people in the U.S. are dealing with three Big Things that impact our physical and mental health; our personal and household financial health; and, our political, social, and moral well-being.

To help deal with this convergence and break the cycle of avoiding dealing with what’s long overdue to confront, we must consider and embrace a new kind of “herd immunity” to consider in this moment, described in a May 2020 JAMA editorial by David Williams and Lisa Cooper.

The Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) explains:

“Herd immunity (or community immunity) occurs when a high percentage of the community is immune to a disease (through vaccination and/or prior illness), making the spread of this disease from person to person unlikely. Vaccines prevent many dangerous and deadly diseases. Herd immunity protects the most vulnerable members of our population. If enough people are vaccinated against dangerous diseases, those who are susceptible and cannot get vaccinated are protected because the germ will not be able to ‘find’ those susceptible individuals.”

Williams and Cooper start their essay with the macro statistic: “In adulthood, black individuals have higher death rates than white persons for most of the leading causes of death.”

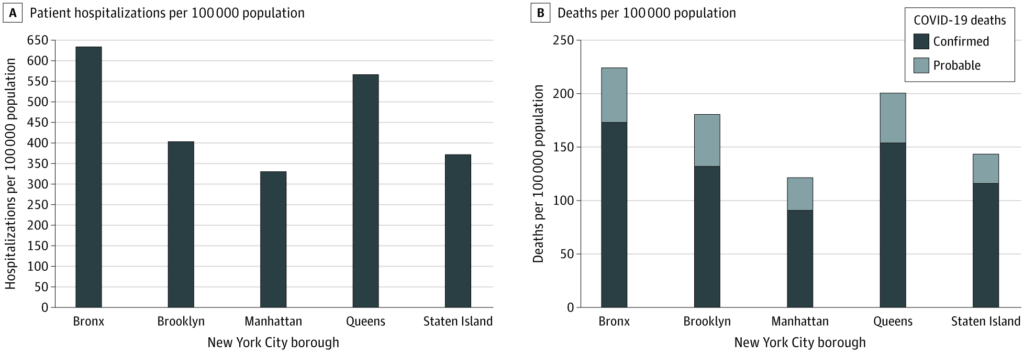

Their article focuses on the research to-date on rates of incidence and mortality due to COVID-19 in communities with higher black populations compared with white. One study, by Wadhera et. al., found risks linked to COVID-19 significantly varied by borough of residence in New York City. More affluent ZIP codes which had predominantly white residents had the lowest rates of COVID-19, even with higher population density. These data are shown in the bar chart for patient hospitalizations and deaths per 100,000 population in the five boroughs of NYC.

Their article focuses on the research to-date on rates of incidence and mortality due to COVID-19 in communities with higher black populations compared with white. One study, by Wadhera et. al., found risks linked to COVID-19 significantly varied by borough of residence in New York City. More affluent ZIP codes which had predominantly white residents had the lowest rates of COVID-19, even with higher population density. These data are shown in the bar chart for patient hospitalizations and deaths per 100,000 population in the five boroughs of NYC.

A similar finding in JAMA was also published, identifying higher COVID-19 rates among black people living in 4 highly-concentrated neighborhoods in Chicago. Dr. Yancy writes: “The US has needed a trigger to fully address health care disparities; COVID-19 may be that bellwether event.”

How to flatten the curve of racial disparities in health? Williams and Cooper wonder. In the short-run, there are immediate needs for housing, food, and economic assistance for those at most-risk for COVID and its accompanying negative financial impacts. In the longer range, “systematic, comprehensive and coordinate investments should be prioritized that create healthy homes and communities and provide ladders of opportunity (i.e., education and gainful employment) to ensure that all individuals in the US have access to choices that facilitate good health,” the authors recommend.

These tactics would provide a sort of “vaccine” to improve population health and create herd immunity against inequities in health, they propose.

This re-positions and -defines “herd immunity” in a contemporary way, recognizing that bolstering social determinants of health can “immunize” America from further divisions in public health and social/community chasms.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.