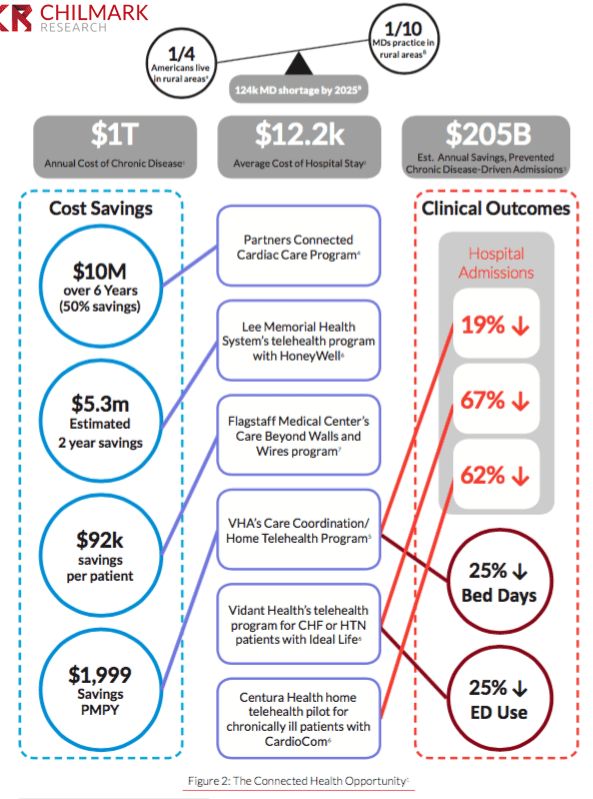

Remote Monitoring CAN work – but that doesn’t mean it WILL. (Figure from Chilmark’s Connected Health Report)

The results of a six-month study on the impact of connected devices on chronically ill patients are in – and they’re not good.

The Scripps Translational Science Institute found that in a randomized control trial (RCT) comparing chronic care using connected devices against standard disease management models, the devices had no discernible impact on healthcare utilization, and little impact on health self-management.

Brian at Mobihealthnews has compiled a nice summary of the reaction from industry leaders on Twitter – equal parts defensive, dismissive, and even some smug satisfaction given today’s hype around these devices. Several pundits, including study author Dr. Eric Topol himself, have offered up insights (and excuses) as to what’s happening here: the study wasn’t long enough, data are inconclusive, technology has evolved since 2012, etc.

We’ll offer another explanation.

Simply put, what works for clinical whitecoats and industry whitepapers won’t always work amidst the vivid colors of the real world. Digital Hypemen take note: Just strapping technology onto a patient will not make them healthier. Our new connected health report finds there have been several successful studies (see the infographic to the right)– but few successfully scaled programs. The single most salient insight for me personally was that vendors and their customers play hot potato when it comes to taking a leadership role in onboarding patients and customizing remote patient monitoring (RPM) “kits” to fit into patients’ lives. The dismal outcomes of the Scripps study is a confirmation that this may be the lynchpin to successful deployment of remote patient monitoring programs moving forward. We looked at the Scripps study in more detail and uncovered a few specific areas where the study design came up short.

The Limitations of Claims Data

Claims data reminds us of the old joke about the man on the street looking for his keys under a streetlamp. A second person passing by offers assistance, asking if he’s dropped them nearby. The first man responds that no, he didn’t – but it’s well-lit on this side of the street so he’s looking for them here.

People choose to see a doctor based on a multitude of reasons, many of which have nothing to do with their health status: time, schedules, costs, locations, and a growing list of convenient alternatives. How many of us simply ask a doctor in the family instead (or these days, the IT geek or insurance wonk)? Even if we put aside about the growing financial disincentive to use health insurance, we’ve moved into an era of invisible, ubiquitous utilization, of Minute Clinics, telehealth, YouTube, WebMD, and Dr. Oz. Health, illness, and the rest of life happens outside of the facility –isn’t that the whole point of remote patient monitoring? That researchers limited themselves to measuring only in-facility utilization is a head-scratching oversight.

What was the impact on study participants’ grocery store purchases, or what they bought for lunch at work? On what else they bought at the pharmacy when they renewed their prescriptions? On visits to the gym? On their behavior on a rainy day? On what they searched or bought online, or shared on social media? In 2016, researchers deserve a SMAC the next time they propose studying patient engagement using claims data.

Ignoring Patient Workflow

Participants were provided study phones, rather than allowed to use their own phones. A smartphone is not the same as YOUR smartphone. Our phones are an extension of ourselves, inextricably linked with our behavior, moods, and decisions for hours and hours every day. The baseline for impact on “real” patient behavior is already off. If you were in a study and you wanted to Google something health-related, would you use the phone they gave you, or your own phone? Were disease management staff contacting people on their study phone, or on their regular mobile? While this may be a small issue considering what the study was assessing, to us it seems a missed opportunity to understand real world behavior. We’re thrilled to see companies like Sherbit partnering with Harvard Medical School researchers to explore how real world smartphone data can play a role in improving chronic disease care outcomes.

Requiring patients to set up and log into a third party portal (QualComm’s Healthy Circles) on a third-party phone was another left turn. Remote monitoring is not about the devices– it’s about stitching them seamlessly into the fabric of patients’ everyday lives. Put differently, this is a workflow problem exacerbated by software. We suspect patients had two (or more) additional portals to the one designed for the study – one from their insurer, and one from their doctor. In the context of a digital health study, it’s safe to say the petri dish was probably contaminated. It’s only the occasional vendor, like DatStat, who’s trying to bring a seamless, mobile approach to patient data collection from the world of research into clinical care.

Pushing educational content to patients through a designated online portal is a mediocre, outdated approach. A better move might have been to obtain consent to track their smartphone or web searches that contained certain keywords (e.g. diet, sleep, carbs, salt, blood pressure, etc.) and combining this with automated push of relevant content. This hypothetical opportunity is the type of unique advantage that researchers should aim to leverage in studies like this one. When will vendors and doctors start meeting patients where we are (location, but also era)? We’re hoping Apple’s current hiring spree bodes well for these challenges.

Completely Missing the Point of Sharing Data with Patients

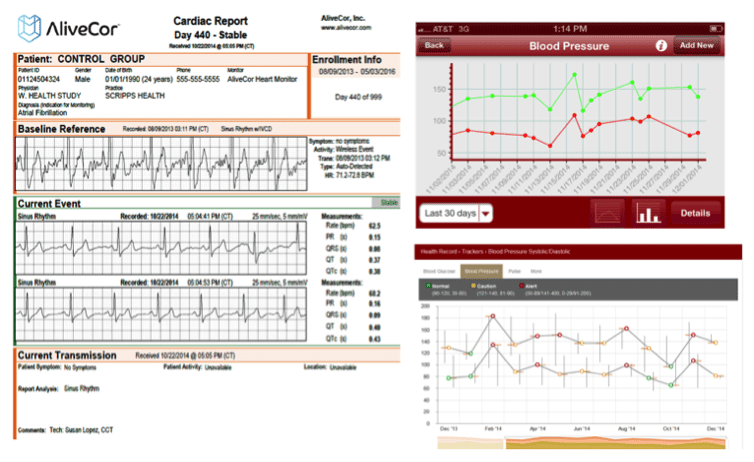

If we want to educate and activate patients, why do data still look like this?

Actual patient data screengrabs from the Study’s Supplemental Methods (https://peerj.com/articles/1554/#supp-2)

This is an old soapbox for us at Chilmark Research; I’ve complained about my useless lab test results at length before. To his credit, Dr. Topol has acknowledged that data visualization could have been better. But over the course of the last five or six years, we are frustrated to see that the typical clinical portal – EMR, Remote Monitoring, Care Management, or other – has hardly changed how it presents data. We must stop throwing low-value data in patients’ faces without making them easy to understand – and medical decorum be damned, even stimulating and fun. The approach taken by industry, and by Scripps researchers, is tantamount to leaving the patient out of the equation rather than bringing them on board the care team. Worst of all – this is the lowest hanging fruit. There are high school web developers who can juice up these visuals to make them slick and compelling, and college pre-meds who can translate these graphs into English. We simply must get better.

For this research, the failure to get this small, simple piece right may have been the study’s biggest flaw. Of course, we openly acknowledge the whole point of research – to learn, and nudge the industry forward step by step, making one mistake at a time in order to improve. This was a groundbreaking study if for no other reason than it pointed out that we have a lot of work left to do.

But when are we going to do it? As long as we insist on measuring data without leveraging its potential to augment patient behavior – and monitor patients without engaging them – we’re buzzing about wireless with one hand wired behind our back.

Editor’s Note: Naveen makes some excellent points but one other I would add is how does the use of RPM enhance patient satisfaction? This is one area where the use of RPM has shown some positive results in past studies. Rather than going to a doctor’s office to have their biometrics recorded, patients do it from home. For many, this is a huge benefit that is often overlooked. -J. Moore

I would propose that legislation be put forward on implementing a model for patient data I call a patient ‘data custodian’, an entity contracted by the patient to hold their health data. Providers, et.al., post (defer ownership) of PHI to the patient’s custodian who then applies privacy rights to the access of such PHI. Properly implemented, the custodian can provide aggregative access to its entire population for purposes of analytics, treatment success/failure, etc., without exposing identity. Individual patient data access would be allowed to patient authorized entities for data allowed by the patient. EHRs, as we now know them, become the interfaces to the patient custodian data, not the siloes they currently are. Having a single interface/site to the patient’s data solves the errors in the study which would have been a simple interface to the patient’s custodian database, populated from the devices.

I believe without a consensus on how to handle patient data and its privacy will doom efforts for patient wearables to ineffective results, at potentially very high costs.

Tim – Thanks for taking the time to leave a message.

Yours is one of the many ideas in healthcare that could make sense in theory, but will take moving mountains to implement in reality. A few reasons why:

1) Medicine is still miles away from acknowledging patients even have a right to their data. See this recent piece in the times: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/us/new-guidelines-nudge-doctors-on-giving-patients-access-to-medical-records.html?_r=0

2) The market is still mastering just giving patients data access through View, Download, Transmit requirements, Blue Button, Open Notes, and so forth. The industry leaders we speak with say that now that this step has gotten some traction, the next step is ramping up patient control of the data – ability to edit it, share it with people, and so forth. This won’t happen in a widespread way for years (and it’s particularly bad at hospitals)

3) Policy around consent for patient data is still muddled. In New York for example, there are numerous levels of consent that patients have to go through. This is well intentioned, but the effect has been to block off access to patient data for clinicians and researchers. This needs to evolve to fit the times we live in.

Lots to work on for sure – I agree that privacy and data ownership is a key part of wearables and remote monitoring. Let’s keep our fingers crossed on this one.

Naveen – I would like to make one more point. If a patient data custodian is accessed and updated by the EHR directly as part of its processing, all of the desired outcomes of interoperability could be accomplished including such goals as patient population management, analytics for treatments, high risk patients, drug discovery and effectiveness, etc. I would think that current aversion to sharing data would disappear when the benefits of sharing are realized.

In the data custodian model, all access is by explicit patient consent which would seem to conform to any state, federal, or otherwise consent legislation.

Tim – agreed. Who’s going to get the EHR vendors to agree to that, and the health systems to sign off on relinquishing control of patient data, has got me stumped : )

Thanks again for being so engaged here. Appreciate it very much.

Cheers –

Naveen

Naveen, great article with great points. The studies I have seen where “it worked” have had very clear roles for the physicians with respect to enrollment and patient interaction (not hot potato with the vendor) and made it so easy for patients to use that it was nearly unavoidable (e.g., some historic Health Buddy studies). Without those pieces of the puzzle in place, it’s all talk and not much more.

Lisa – thanks so much for taking the time to comment. Your perspective is a highly valued one at Chilmark.

Alas everything has changed a bit since those old Kaiser and VA pilots with Bosch in the early 2000’s. The consumer/patient workflow before and after the iPhone is like going from Flintstones to Jetsons. Would encourage you to check out those startups I mentioned – both have pretty novel approaches to the issues above.

Cheers,

Naveen

I couldn’t resist, as much as I tried….you know I like your work, but:

“everything has changed a bit since early 2000” – the VA studies were pumping out huge clinical and financial outcomes before the national contract in 2004 through 2010 (when I stopped being involved – it might have gone on after, but I can’t say for sure). The national contract was only given in 2004, so the argument that “everything changed” in ~10 years feels intellectually lazy. If we use 2010 as the last year, you’re saying “everything has changed in 5 years” – I doubt you believe that.

Also, you’re missing the key point of why Health Buddy worked. We actually had mobile products, web products, and all sorts of technology other than the custom hardware – you’ll be shocked to find out the Jetson stuff never worked as well as the simple hardware (yes even iPhone) — even when it was the stuff I wanted to work on the most… (I wasted more time on one Nextel/Mobile and another TV settop box product than I care to admit!)

It’s also missing the point that it was dailey, digital therapeutics long before the buzz words. It’s a long story, but given what worked – EMR integration, medical device integration, huge clinical and financial outcomes (and even early Blue Button support – it started with the VA!) – it’s weird to see it dismissed just because it pre-dated TechCrunch.

I usually let this go, but I’m a big believer in you, in this site, and in the the startups you mentioned and they are carrying the torch – what they will do over the next few years SHOULD far surpass it, but only if they learn from all our (gazillions) of mistakes. The future is bright because we all need to really think hard on this, take what works from each other, and leave behind what doesn’t. “Everything has changed” doesn’t get us there.

Of course, I’m also super biased here, I’ll admit that. I’ll also admit when I was there company, sometimes the biggest mistakes I made was looking at people before us and discounting it; so I’ve been there, and discounted the past easily before as well. So, there you go – there’s one of many of my mistakes you can skip 🙂

Finally, since I’m being the old grumpy man (Damn it, I’m that guy arn’t I?) I’ll finish like a total pain in the ass – yeah, it’s a nitpick, but please don’t call them “Bosch” outcomes, as they were not involved in any of the VA work – they didn’t even buy the company until 2008, so all the meaningful work with the VA (and everyone else) was done over the previous 8 years. People like Laurie, Scott, Tiffany, Trish, Dave, Curtis and so many more are the reason the VA (and everything else) was as successful as it was.

Thanks again for writing the report. RPM is too important to the future of how healthcare will work to not have people like you really dissecting the outcomes. Keep it going.

Geoff -You know we got nothing but love for the industry’s grumpy old men 🙂

The Bosch comment was indeed, a toss-in on my part, not real analysis. Thanks for sharing the real scoop and correcting the mis-representation. Of course we didn’t mean to misportray or undersell your work.

By “everything has changed” I wasn’t talking about the market conditions or the VA – I referring specifically to smartphones’ impact on us as people – what we do, how we do it, more in the context of us as people, not just patients. I will stand firm on saying that the world today is super-duper different than it was in 2010 from a consumer perspective. That’s right – super, duper different…Uber, amazon, tinder, facetime, etc have permanently changed behavior, expectations, needs. Maybe not for Medicare patients as much – but there are other chronically ill patients out there, too. What may have worked just a few years ago in the context of monitoring patients in their homes/workplaces/cars needs to be shaken up a little (or a lot) to fit into the modern “patient workflow.”

More importantly – and in a different forum – we would love to get the full skinny on what you’ve learned. As you and I have discussed before, the ‘old hands’ can serve as valuable resources for today’s younger entrepreneurs to incorporate valuable insights (market, biz, tech, strategy) into their efforts. If we learned nothing else from the scripps study, it’s that the traditional ways of approaching the digital engagement puzzle aren’t working.

Thanks for commenting.

I think you hit on some very valid points. What stood out to me was the fact that the 65 participants in the monitoring group only accessed the online disease management system, HealthyCircles, roughly nine times each over a six month period. That’s very little engagement with a system that’s supposed to be helping them change the health behaviors related to what they’re monitoring.

Self-monitoring should complement a broader, more comprehensive disease management program and in return the program should support the monitoring devices. Not just by taking the data that’s already accessible via their phones and regurgitating it onto a dashboard (that’s usually ugly and useless, as you’ve noted), but by helping the participant understand their results and how they can be used to influence and motivate their actions.

It’s also important to note that all tracking devices are not equal. Some devices track our actual behaviors (Fitbit, Jawbone, etc) while others track symptoms of our behaviors (blood pressure, blood glucose, etc). If I track my BP and it reads high, then what? I’m now aware that my BP is high and I should do something, but that’s it. I need something else to help change the behaviors that led to my high reading. That’s where the HealthyCircles disease management program should come into play, but clearly it didn’t. If I was at Qualcomm working on the HealthyCircles program, these study results would serve as a red flag for some serious change.

Jason – Thank you for your comment and your insight. Couldn’t agree more…there is probably a dissertation that could be written on how to improve the methods and study design to reflect the real world.

Your comments about HealthyCircles are not unique to QualComm – Going back over the last decade, when has anyone acknowledged that patient portals are a well-designed and stimulating option for patients? We’ve only had modest “success” from the health system’s eyes at best (e.g. KP’s MyChart) – and that was largely driven by communication/secure e-mail features. The point is – if you take a broken approach to interacting with patients (the portal) and slap some neato gizmos on top of it, nothing really changes.

Cheers and please keep that critical eye open – we need more voices like yours to push this thing forward.

Naveen

Naveen –

I think you hit the nail on the head – usability – around both the data and the mechanisms used to collect it is the key to success. Both need to be simple and intuitive, which seems to be a rarity. One suggestion for you on the data side…take a look at a startup called VisualCue (www.visualcue.com). I think they hold the key for making large amounts of data consumable and intuitive. I co-authored an article (unpublished) titled “How the Check Engine Light Will Transform Healthcare” that suggests a user interface like the one offered by VisualCue, combined with real-time data can help each of us better understand our bodies and how to manage our own health.

Robert – thank you for reading and taking the time to comment. Have heard about the concept of a “check engine light” before – gets a thumbs up from our end. Usability is everything (for patients and clinicians). I will take a look!

Hi Naveen. Thanks for the article. This is the first of yours I have read and appreciate the analysis.

I’m working on a unique business model and would be interested in your perspective. In addition to many of the issues you’ve noted along with the commenters, one key piece missing in the industry is to flip how we think about consumers, their role in the process, and the opportunity to leverage behavioral economics.

First, I wonder how this study would have been different if people were given choices of devices, programs, or interventions – other than the typical healthcare A/B Yes/No decision to engage or not engage?

Second, given the immense waste in healthcare, if we think of consumers as owners of that waste (they are recipients of the care after all) and turn them into the assets upon which companies offering these programs will offer money and services in exchange for engagement, I believe we could transform engagement.

Why would companies do this? We offer them a shared savings contract with the payer and individual level data, companies could value each person uniquely and craft personalized bids include money and expectations for engagement. Then the person could select the one they value most – be it in-home care, in-home monitoring, devices, weekly call with care manager, etc.

This approach gives consumers substantial choices and incentives to elect something and participate. This gives companies opportunities to bid for individuals and the upside potential of a shared savings contract. This allows payers to share the risk and deliver a better experience to members by giving them choices of high quality programs.

I’d welcome a chance to discuss this approach with you sometime. Please shoot me a note if you are willing.

Interesting concept Josh. Agree with some of your ideas. Giving consumers more “ownership” in their health to date has been a little bit of a failure, in part because it’s being done indirectly through the payment/insurance arm, rather than by the direct care arm. So far one major adverse side effect has been that people put off or avoid necessary, high value care in order to save money. So there would have to be a strong educational component. Also think, for various reasons, employer market would be the proper place to try this out. You can contact me at naveen at chilmark research dot com if you’d like to discuss further.

Thank you for this insight, we all greatly appreciate it.

Technology is simply one of the tools needed to support individuals with data to build confidence in their knowledge. I agree that if we want individuals to be confident in their self-management and to be activated in shared decision making and driving their own care they need these tools. More importantly individuals and their caregivers and loved ones need support of coaches to help with misinformation and behavior changes needed to be empowered, not just about facts and data, but to know and have the ability to make informed decisions, that are personalized to the individual. Coaching needs to be available when the individuals and their loved ones needs it.

Coaching keeps individuals accountable on their collaborative health plans as they using data as part of the recipe to alter what needs to be done and track, monitor, and trigger exacerbations and other outcomes.

Effective models of care should have the ability to offer coaching one on one when individuals require it- whether face to face or more efficiently via technology (text, video, phone….) I think the more creative we are with the who coaches is where the secret sauce might be.

Developing teams and algorithms to assign the right skill set for that at the right time and place is how technology can enhance the new models. Technology is a critical tool- but only when utilized as a tool not a solution.

Hello Deb,

Thank you for providing some valuable insights and contributing to this conversation.

Agree completely that technology is but an enabler to engagement, one that can be quite effective in augmenting personal relationships with a care provider, clinician, social worker, care navigator, etc. especially when one or a loved one is in a crisis situation. The healthcare system, if we can even call it that is difficult to effectively navigate when one is well. When one is ill, it can be nearly impossible.

There are a number of companies that are beginning to offer such services – some more heavily tech-enabled then others e.g., Twine Health, Accolade, Blueprint HealthIT, etc. Payers & employers have also been trying to tackle this issue as well for years to direct their members/employees to high value care facilities and follow-on support for chronic disease mgmt.

The main point of this post though was to simply point out that as a society, our efforts to drive patient engagement, via mandated patient portals, on an industry that simply was not ready to fully enable and support such a move has created a far less than ideal outcome for patients, clinicians, care givers and society.