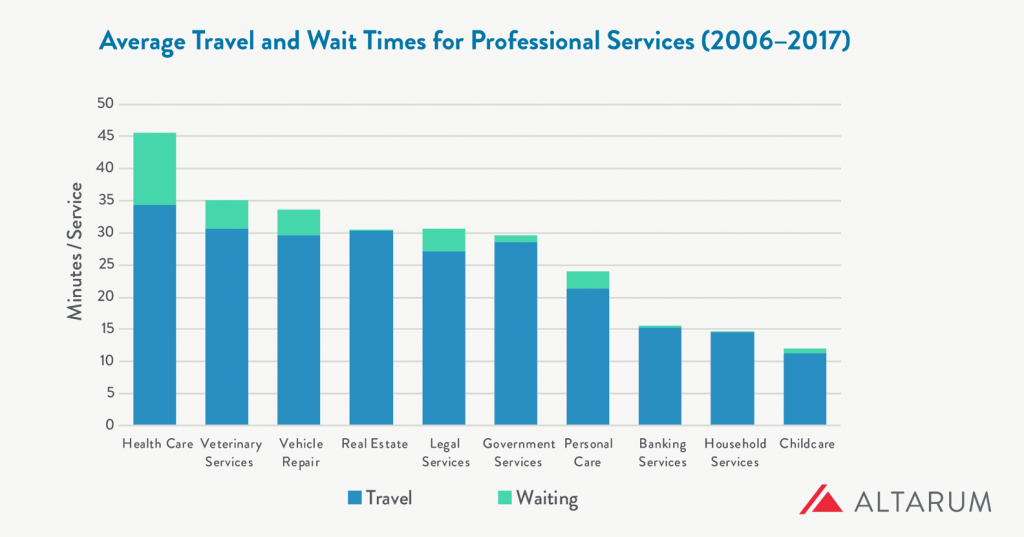

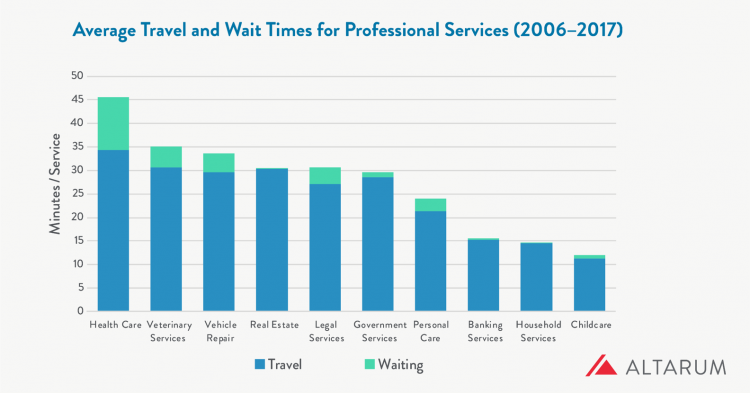

What industry compels its “consumers” to wait longer and travel further for services more than any other in a person’s daily life?

That would be health care, a report from Altarum notes.

People travel further and wait longer for medical services than for veterinary care (second in this line-up), auto repair, banking, and household services.

The annual opportunity cost for travel and wait time in health care is $89 billion, Altarum estimated.

For the average person, that translates to 34 minutes of travel time and 11 minutes waiting time at the provider’s office.

In terms of personal opportunity costs, Altarum gauged the following lost-times:

- A working person loses 90 minutes of work-time

- A working person loses 37 minutes of leisure time

- A person who’s not in the labor force loses 74 minutes of leisure time.

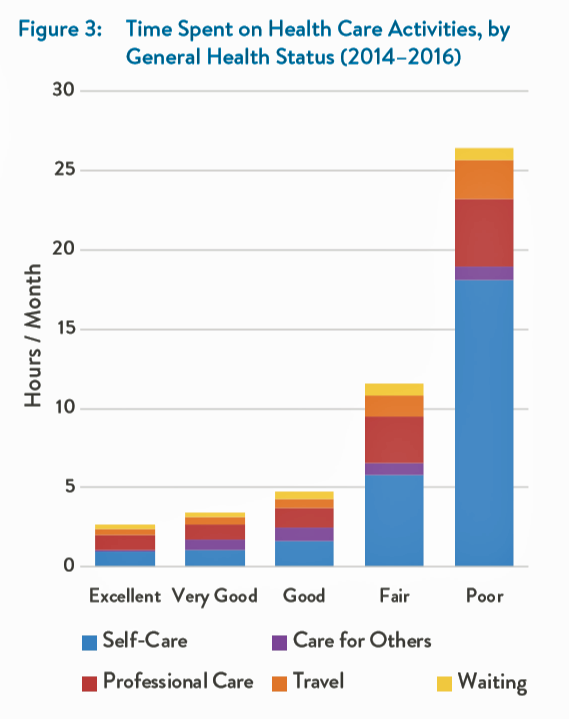

Read this last bullet point again. Then, take a look at this layered bar chart which illustrates the direct straight line relationship between the time a person spends on health care activities and that person’s health status. It’s simple to see that people in poor health spend much more time in a day on self-care than healthier people. Sicker people also spend much more time traveling to health care appointments.

The person in poor health would also more likely be unemployed or out of the labor force, which underscores the importance of the travel-time challenge.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I snapped this photo, a promotional ad from Lyft, at HIMSS19 in Orlando two weeks ago. This was the first image that greeted me as I entered the Orange County Convention Center to retrieve my badge for the conference.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I snapped this photo, a promotional ad from Lyft, at HIMSS19 in Orlando two weeks ago. This was the first image that greeted me as I entered the Orange County Convention Center to retrieve my badge for the conference.

“90% of seniors say access to Lyft improves their quality of life,” the company gleaned from a consumer survey they conducted and reported in Fast Company. Check out the brand associated with this message at the bottom of the poster: it’s from AARP, which is an association of 38 million people over the age of 50, a key bloc of consumers looking to age well and prosper as long as they can.

There’s travel time, and there’s quality time. Considering the “poor health” bar in the graph, we can see the opportunity for telehealth and home visits to people who may have mobility and other challenges leaving the home space. Our homes are evolving into our health hubs — truly our “medical homes,” which have been formally defined as a primary care gatekeeper’s office. Why should that be, in a physical sense?

An article published in Health Services Research in August 2018 talks about Trends in the Types of Usual Sources of Care: A Shift from People to Places or Nothing at All. The Accenture health care team shared this with me at HIMSS19 in the context of their research into consumer demands for alternate sites of medical services, from retail clinics to virtual platforms.

“The positive, salutary effects of having a USC have been documented for decades,” the authors note. “Usual Sources of Care” (USCs) have been associated with higher quality, reduced unmet needs, and fewer health disparities, previous research has found. Even for uninsured people in the U.S., having a usual point of contact for health care is an on-ramp to preventive services and physician visits.

But what if the in-person, bricks-and-mortar model shifts to more virtual, more local, more convenient channels of care? What might a USC in contemporary, digitally-enabled formats look and feel like? What if that “place” was our home, first and foremost?

That’s what some of us are working on these days. Stay tuned…

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.